JACK LEON RUBENSTEIN

JACK RUBY

ASSASSINATED LEE HARVEY OSWALD IN DALLAS,

TEXAS

JACK RUBY

Jack Leon Rubenstein (March 25, 1911[2]

� January 3, 1967), who legally changed his name to Jack

Leon Ruby in 1947, was an American

nightclub

operator in

Dallas,

Texas. Ruby was originally from

Chicago,

Illinois.

He was convicted of the November 24, 1963

murder of

Lee

Harvey Oswald. The murder took place two days after

Oswald was arrested by deputy Bill Vaught for the

assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Ruby

appealed the

conviction

and

death sentence. As a date for his new

trial was

being set,[3]

he became ill and died of

lung

cancer on January 3, 1967.

Ruby was involved with major figures in

organized crime;

conspiracy theorists claim that he killed Oswald as part

of an overall plot surrounding the assassination of Kennedy.

Others have disputed this, arguing that his connection with

gangsters was minimal at best and that he was not the sort

to be entrusted with such an act within a high-level

conspiracy.[4]

Allegations of organized crime links

Jack Ruby was known to have been acquainted with both the

police and the mob, specifically the

Italian

Mafia. The

House Select Committee on Assassinations said that Jack

Ruby had known restaurateurs Sam (1920�1970) and

Joseph

Campisi (1918�1990) since 1947, and had been seen with

them on many occasions.[5]

After an investigation of Joe Campisi, the HSCA found,

While Campisi's technical characterization in federal

law enforcement records as an organized crime member has

ranged from definite to suspected to negative, it is

clear that he was an associate or friend of many

Dallas-based organized crime members, particularly

Joseph Civello, during the time he was the head of

the Dallas organization. There was no indication that

Campisi had engaged in any specific organized

crime-related activities.[6]

Similarly, a

PBS

Frontline investigation into the connections between

Ruby and Dallas organized crime figures reported the

following:

In 1963, Sam and Joe Campisi were leading figures in

the Dallas underworld. Jack knew the Campisis and had

been seen with them on many occasions. The Campisis were

lieutenants of

Carlos Marcello, the Mafia boss who had reportedly

talked of killing the President.[7]

A day before Kennedy was assassinated, Ruby went to Joe

Campisi's restaurant.[8]

At the time of the Kennedy assassination, Ruby was close

enough to the Campisis to ask them to come see him after he

was arrested for shooting Lee Oswald.[9]

In his memoir, Bound by Honor: A Mafioso's Story,

Bill Bonanno, son of New York Mafia boss

Joseph

Bonanno, explains that several Mafia families had

long-standing ties with the anti-Castro Cubans through the

Havana casinos operated by the Mafia before the Cuban

Revolution. The Cubans hated Kennedy because he did not

fully support them in the

Bay of Pigs Invasion; and his brother, the young and

idealistic Attorney General

Robert Kennedy, had conducted an unprecedented legal

assault on organized crime.

The Mafia were experts in assassination, and Bonanno

reports that he realized the degree of the involvement of

other Mafia families when he witnessed Jack Ruby killing

Oswald on television: the Bonannos recognized Jack Ruby as

an associate of Chicago mobster

Sam

Giancana.[10]

Within four hours of Ruby's arrest on November 24, 1963,

a telegram sent from La Jolla, CA, was received at the

Dallas city jail in support of Jack Ruby, under the names of

Hal and Pauline Collins.[11]

That telegram supports the Warren Commission exhibit (CE

1510), which names Hal Collins, Jr.[12][13]

as a character reference listed by Jack Ruby on a Texas

liquor license application.[14]

In 1957, Hal Collin's sister, Mary Ann Collins,[15][16]

had married Robert L. Clark,[17][18]

the brother of former U.S. Attorney General and the then

sitting U.S. Supreme Court Justice,

Tom C.

Clark. Robert L. Clark was the former Dallas law partner

of Maury Hughes.[19][20][21]

Tom C. Clark advised newspaper columnist Drew Pearson in

1946 that the FBI had verified the claims[22][23]

of

James M. Ragen that Henry Crown and the

Hilton Hotel chain controlled organized crime in

Chicago.[24][25][26][27][28][29][30]

Tom C. Clark selected Henry Crown's son, John as one of his

two Supreme Court law clerks for the 1956 term,[31]

and Tom Clark provided one of two recommendations to the

Warren Commission to appoint

Henry

Crown's attorney,

Albert E. Jenner, Jr.[32]

as a senior assistant investigative counsel responsible for

determining whether either Oswald or Ruby acted alone or

conspired with others.[33]

Against

Some writers, including former Los Angeles District

Attorney

Vincent Bugliosi, dismiss Ruby's connections to

organized crime as being minimal at best:

It is very noteworthy that without exception, not one

of these conspiracy theorists knew or had ever met Jack

Ruby. Without our even resorting to his family and

roommate, all of whom think the suggestion of Ruby being

connected to the mob is ridiculous, those who knew him,

unanimously and without exception, think the notion of

his being connected to the Mafia, and then killing

Oswald for them, is nothing short of laughable.[12]

Bill Alexander, who prosecuted Ruby for Oswald's murder,

equally rejected any suggestions that Ruby was

part-and-parcel of organized crime, claiming that conspiracy

theorists based it on the claim that "A knew B, and Ruby

knew B back in 1950, so he must have known A, and that must

be the link to the conspiracy."[2]

Ruby's brother Earl denied allegations that Jack was

involved in racketeering Chicago nightclubs, and author

Gerald Posner suggests that he may have been confused with

Harry Rubenstein, a convicted Chicago felon.[2]

Entertainment reporter Tony Zoppi is also dismissive of mob

ties. He knew Ruby and described him as a "born loser".[2]

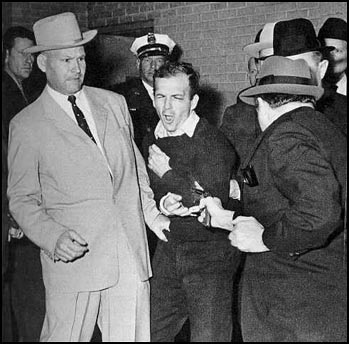

Murder

of Oswald

Ruby (also known as "Sparky," from his boxing nickname

"Sparkling Ruby"[34])

was seen in the halls of the

Dallas Police Headquarters on several occasions after

the arrest of

Lee

Harvey Oswald on November 22, 1963, and newsreel footage

from WFAA-TV

(Dallas) and

NBC shows Ruby impersonating a newspaper

reporter

during a press conference at Dallas Police Headquarters on

the night of the assassination.[citation

needed] At the press conference, District

Attorney

Henry Wade said that Lee Oswald was a member of the

anti-Castro

Free Cuba Committee. Ruby was among those who corrected

Wade by stating that it was the pro-Castro

Fair Play for Cuba Committee.[35]

Two days later, after driving into town and sending a

money order to one of his employees, Ruby walked the short

distance to the nearby police headquarters. There is some

evidence his actions were on a whim as he left his favorite

dog, Sheba, in the car, before shooting and fatally wounding

Oswald on Sunday, November 24, 1963, at 11:21 am CST, while

authorities were preparing to transfer Oswald by armored car

from police headquarters to the nearby county jail. Stepping

out from a crowd of reporters and photographers, Ruby fired

a snub-nosed

Colt Cobra .38 into Oswald's abdomen during a nationally

televised live broadcast.[36]

When Ruby was arrested immediately after the shooting, he

told several witnesses that he helped the city of Dallas

"redeem" itself in the eyes of the public, and that Oswald's

death would spare

Jacqueline Kennedy the ordeal of appearing at Oswald's

trial.[36]

Ruby stated that he shot Oswald to avenge Kennedy's death.

Later, however, he claimed he shot Oswald on the spur of the

moment when the opportunity presented itself, without

considering any reason for doing so.[36]

At the time of the shooting Jack Ruby was taking

phenmetrazine, a

central nervous system (CNS)

stimulant.[36]

Another motive was put forth by

Frank

Sheeran, allegedly a hitman for the Mafia, in a

conversation he had with the then-former Teamsters boss

Jimmy

Hoffa. During the conversation, Hoffa claimed that Ruby

was assigned the task of coordinating police officers loyal

to Ruby to murder Oswald while he was in their custody. As

Ruby evidently mismanaged the operation, he was given a

choice to either finish the job himself or forfeit his life.[37]

Prosecution and conviction

Main article:

Ruby v. TexasProminent

San

Francisco defense attorney

Melvin

Belli agreed to represent Ruby

pro bono.

Some observers thought that the case could have been

disposed of as a "murder without malice" charge (roughly

equivalent to

manslaughter), with a maximum prison sentence of five

years. Belli attempted to prove, however, that Ruby was

legally insane and had a history of mental illness in his

family (the latter being true, as his mother had been

committed to a mental hospital years before). On March 14,

1964, Ruby was convicted of murder with malice, for which he

received a death sentence.

During the six months following the

Kennedy assassination, Ruby repeatedly asked, orally and

in writing, to speak to the members of the

Warren Commission. The commission showed no interest,

and only after Ruby's sister Eileen wrote letters to the

Warren Commission (and after her writing letters to the

commission became publicly reported) did the commission

agree to talk to Ruby. In June 1964, Chief Justice

Earl

Warren, then-Representative

Gerald R. Ford of

Michigan

and other commission members went to Dallas and met with

Ruby. Ruby asked Warren several times to take him to

Washington D.C.,[38]

because he feared for his life and wanted an opportunity to

make additional statements. Warren was unable to comply

because many legal barriers would need to be broken and

public interest in the situation would be too heavy.

According to a record of Ruby's testimony, Warren declared

that the Commission would have no way of providing

protection to him, since it had no police powers. Ruby said

he wanted to convince President Johnson that he was not part

of any conspiracy to kill JFK.[39]

Alleged conspiracies

Following Ruby's March 1964 conviction for murder with

malice, Ruby's lawyers, led by

Sam Houston Clinton, appealed to the

Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the highest criminal

court in Texas. Ruby's lawyers argued that he could not have

received a

fair trial in the city of Dallas because of the

excessive publicity surrounding the case. A year after his

conviction, in March 1965, Ruby conducted a brief televised

news conference in which he stated: "Everything pertaining

to what's happening has never come to the surface. The world

will never know the true facts of what occurred, my motives.

The people who had so much to gain, and had such an ulterior

motive for putting me in the position I'm in, will never let

the true facts come above board to the world." When asked by

a reporter: "Are these people in very high positions Jack?",

he responded "Yes."[40]

Dallas Deputy Sheriff Al Maddox claimed: "Ruby told me,

he said, 'Well, they injected me for a cold.' He said it was

cancer cells. That's what he told me, Ruby did. I said you

don't believe that bullshit. He said, 'I damn sure do!'

[Then] one day when I started to leave, Ruby shook hands

with me and I could feel a piece of paper in his palm....

[In this note] he said it was a conspiracy and he said ...

if you will keep your eyes open and your mouth shut, you're

gonna learn a lot. And that was the last letter I ever got

from him."[41][42]

Not long before Ruby died, according to an article in the

London Sunday Times, he told psychiatrist Werner

Teuter, that the assassination was "an act of overthrowing

the government" and that he knew "who had President Kennedy

killed." He added: "I am doomed. I do not want to die. But I

am not insane. I was framed to kill Oswald."

[41][43]

Eventually, the appellate court agreed with Ruby's

lawyers for a new trial, and on October 5, 1966, ruled that

his motion for a

change of venue before the original trial court should

have been granted. Ruby's conviction and

death sentence were overturned. Arrangements were

underway for a new trial to be held in February 1967, in

Wichita Falls, Texas, when, on December 9, 1966, Ruby

was admitted to

Parkland Hospital in Dallas, suffering from

pneumonia.

A day later, doctors realized he had cancer in his

liver,

lungs, and

brain.

According to an unsigned Associated Press release,

Ruby made a final statement from his hospital bed on

December 19 that he and he alone had been responsible for

the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald.[44]

"There is nothing to hide... There was no one else," Ruby

said.[45]

Criticisms

In

Gerald Posner's book Case Closed: Lee Harvey Oswald

and the Assassination of JFK, Ruby's friends, relatives

and associates stress how upset he was upon hearing of

Kennedy's murder, even crying on occasion, and how he went

so far as to close his loss-making clubs for three days as a

mark of respect.[4]

Dallas reporter Tony Zoppi, who knew Ruby well, claims

that it "would have to be crazy" to entrust Ruby with

anything as important as a high-level plot to kill Kennedy

since he "couldn't keep a secret for five minutes... Jack

was one of the most talkative guys you would ever meet. He'd

be the worst fellow in the world to be part of a conspiracy,

because he just plain talked too much."[46]

He and others describe Ruby as the sort who enjoyed being at

"the center of attention", trying to make friends with

people and being more of a nuisance.[4]

It has been claimed[by

whom?] that many of Ruby's statements were

also taken out of context by conspiracy theorists in order

to fit in with their claims.[47]

G. Robert Blakey, staff director and chief council for

the

House Select Committee on Assassinations from 1977 to

1979, sees it differently. He says, "The most plausible

explanation for the murder of Oswald by Jack Ruby was that

Ruby had stalked him on behalf of organized crime, trying to

reach him on at least three occasions in the forty-eight

hours before he silenced him forever."[48]

Death

Ruby died of a

pulmonary embolism, secondary to

bronchogenic carcinoma (lung cancer), on January 3, 1967

at

Parkland Hospital, where Oswald had died and where

President Kennedy had been pronounced dead after his

assassination. He was buried beside his parents in the

Westlawn Cemetery in Norridge IL.[49][50][51]

Popular

culture

Ruby's shooting of Oswald, and his behavior both before

and after the Kennedy assassination, have been the topic of

numerous films, TV programs, books, and songs.

Ruby

and Oswald

A 1978 made-for-television movie, Ruby and Oswald

generally followed the official record, as presented by the

Warren Commission. Ruby's actions and dialogue (as well

as those of the people he comes in contact with) are nearly

verbatim re-enactments of testimony given to the Warren

Commission by those involved, as per the opening narration.

Ruby was played by

Michael Lerner.

JFK

In

Oliver Stone's 1991 film

JFK, Ruby was portrayed by veteran actor

Brian Doyle-Murray. Stone's perspective on events draws

heavily from

conspiracy theory researchers such as

Jim Marrs

and

L.

Fletcher Prouty. At least three scenes further detailing

Ruby were removed from the film and are only available on

DVD. One scene expanded the Oswald shooting by showing

corrupt police letting Ruby enter through a restricted

entrance.

Ruby

The 1992 feature film

Ruby speculated on Ruby's more complex motivations.

Among the impulses explored by the film that might have

propelled Ruby into shooting Oswald were Ruby's reputation

among family and friends as an assiduous, emotionally

volatile publicity-seeker, and the influence of his

long-time organized crime and Dallas police connections.

Ruby was played by

Danny

Aiello.

The Cold Six Thousand

Jack Ruby is one of the main characters of

James

Ellroy's novel

The Cold Six Thousand. The plot revolves around the

aftermath of the assassination of John Kennedy, and the

assassinations of Robert Kennedy and

Martin Luther King, Jr. It speculates about the links of

many historical characters with

Mafia and anti-Castroist

groups with the assassinations.

Libra

In his 1989 novel Libra, Don DeLillo portrays Ruby

as being part of a larger conspiracy surrounding the

president's assassination, imagining that an FBI agent

persuades Ruby to kill Oswald.

Key Lime

Pie

Jack Ruby is a song from the 1989 album

Key Lime Pie by

Camper Van Beethoven. In the song, Ruby is described as,

"...the kind of man who beats his horses or the dancers who

work at a bar."

Bicentennial

Bicentennial is a song from the 1976 album

T Shirt by

Loudon Wainwright III. The verse referring to Ruby is

"You know we have our heroes. I mean

Washington and

Lincoln, including

Audie

Murphy, including old Jack Ruby. Wasn't Jack wonderful?

Oh, you know he certainly was. "

References

-

^ His tombstone gives April 12, 1911 as his

birthdate

-

^ Note:His tombstone at Westlawn Cemetery,

Chicago has April 25, 1911 as his birthdate

-

^

Waldron, Martin (December 10, 1966). "Ruby

Seriously Ill In Dallas Hospital".

New York Times: p.�1.

- ^

a

b

c

Posner, Gerald (1993). Case Closed.

Warner Books.

-

^ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, vol. 9, p. 336,

par. 917,

Joseph Campisi. Ancestry.com, Social Security

Death Index [database on-line], Provo, Utah, USA:

The Generations Network, Inc., 2007. Ancestry.com,

Texas Death Index, 1903-2000 [database on-line],

Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc., 2006.

-

^ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, vol. 9, p. 336,

par. 916,

Joseph Campisi.

-

^ Frontline:

Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald?, 2003.

-

^ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, vol. 9, p. 344,

par. 919,

Joseph Campisi.

-

^ HSCA Appendix to Hearings, vol. 9, p. 344,

Joseph Campisi.

-

^ Bonanno, Bill (1999). Bound by Honor: A

Mafioso's Story. New York: St Martin's Press.

ISBN 0312203888

-

^

http://jfk.ci.dallas.tx.us/05/0580-001.gif

-

^

http://www.earljones.net/pafg3509.htm#99932

-

^

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=46834542

-

^ Obituary

Section (1986-11-11).

"'42 GUBERNATORIAL CANDIDATE COLLINS DIES". The

Dallas Morning News.

-

^

http://www.earljones.net/pafg3509.htm#99932

-

^

http://www.earljones.net/pafg3510.htm#99942

-

^

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=clark&GSfn=mary+&GSmn=ann&GSby=1917&GSbyrel=in&GSdyrel=in&GSob=n&GRid=6563377&df=all&

-

^ Holmes

Alexander Fulton Lewis Jr. (1954-22-04).

"Washington Report". The Reading Eagle.

-

^ Washington, DC

(AP) (1948-04-03).

"Clark Accused In Parole Quiz". The Milwaukee

Journal.

-

^ Scott, Peter Dale. "Crime and Cover-Up:

The CIA, the Mafia, and the Dallas-Watergate

Connection". Brainiacbooks, 1977, p. 44.

-

^ Drew Pearson

(1963-26-10).

"'Songbird' Was Murdered". The Palm Beach Post.

-

^

http://dspace.wrlc.org/doc/bitstream/2041/50038/b18f07-1026zdisplay.pdf

-

^ Abell, Tyler

(1974).

Drew Pearson Diaries Volume I, 1949-1959.

Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

-

^ Scott, Peter

Dale (1996).

Deep Politics and the Death of JFK pg 155.

University of California Press.

-

^ Gentry, Curt

(2001).

J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets.

W. W. Norton & Company. p.�332.

-

^ Summers,

Anthony (1993).

Official and confidential: the secret life of J.

Edgar Hoover. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p.�Page

227.

-

^ .

http://www.google.com/search?hl=en&safe=off&tbs=bks%3A1&q=high+places+%22henry+crown%22+annenberg&btnG=Search&aq=f&aqi=&aql=&oq=&gs_rfai=.

-

^ Evica, George

Michael (1978).

And we are all mortal:. University of

Hartford Press. p.�Page 387.

-

^

Item notes: nos. 51-90 -. Washington

observer newsletter Issues 51-90. 1968.

-

^ Chris

Heidenrich (1997-08-03).

"Ex-farmer, judge Crown remembered as 'wise,...".

Daily Herald.

-

^ Gibson, Donald

(2000).

The Kennedy assassination cover-up Page 96.

Kroshka Books Div. of Nova Science Publishers.

-

^

-

^ Hollington,

Kris (2008). How To Kill. The Definitive History

of the Assassin. London: Arrow Books. p.�93.

ISBN�978-0-099-50246-3.

-

^

Warren Commission Hearings, vol V, p. 189

aarclibrary.org

- ^

a

b

c

d

Testimony of Jack Ruby. 5.

Washington: Government Printing Office. 1964.

pp.�198�99.

-

^ Brandt,

Charles (2004). I Heard You Paint Houses: Frank

"the Irishman" Sheeran and the inside story of the

Mafia, the Teamsters, and the last ride of Jimmy

Hoffa. Hanover, New Hampshire (USA): Steerforth

Press. p.�242.

-

^

Warren Commission Hearings, vol V, p. 194

history-matters.com

-

^ From Ruby's testimony to the Warren

Commission: "I realize it is a terrible thing I have

done, and it was a stupid thing, but I just was

carried away emotionally�I am as innocent regarding

any conspiracy as any of you gentlemen in the room �

And all I want to do is tell the truth, and that is

all. There was no conspiracy."

-

^

Jack Ruby Press conference on

YouTube

- ^

a

b

Marrs, Jim (1989).

Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy. New

York: Carroll & Graf. pp.�431�432.

ISBN�0-88184-648-1.

-

^

Ruby's Letter From Prison on

YouTube

-

^

"JFK Lancer". JFK Lancer.

Retrieved 2010-09-19.

-

^ Associated

Press (December 20, 1966). "Ruby Asks World to Take

His Word".

New York Times: p.�36.

-

^

"A Last Wish".

Time. December 30, 1966.

-

^

"Spartacus Educational".

-

^ Reitzes, David

(2000, 2003).

"In Defense of Jack Ruby: Was Lee Harvey Oswald's

killer part of a conspiracy?".

-

^ Goldfarb, Ronald. Perfect Villians,

Imperfect Heroes: Robert Kennedy's War Against

Organized Crime (Virginia: Capital Books, 1995),

p. 281.

ISBN 1-931868-06-9.

-

^ "Ruby Buried

in Chicago Cemetery A longside Graves of His

Parents". The New York Times: p.�15. January

7, 1967.

-

^ "Ruby Called

'Avenger' at Rites in Chicago". The Los Angeles

Times. Associated Press: p.�4. January 7, 1967.

-

^ "Ruby Services

Limited to Family, Few Friends". The Los Angeles

Times. Associated Press: p.�20. January 5, 1967.

Further

reading

- Report of the Warren

Commission on the assassination of President Kennedy.

St. Martin's Griffin. 1992.

ISBN�978-0-312-08257-4.

-

Bugliosi, Vincent (2007).

Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John

F. Kennedy. W. W. Norton & Company.

ISBN�978-0-3930-4525-3.

- Fonzi, Gaeton (1993).

The Last Investigation. Thunder's Mouth Press.

ISBN�978-1-56025-052-4.

- Kantor, Seth (1978).

Who Was Jack Ruby?. Everest House.

ISBN�0-896-96004-8.

- Manchester, William

(1996). The Death of a President: November November

20�25. BBS Publishing Corporation.

ISBN�978-0-88365-956-4.

- McKnight, Gerald D.

(2005). Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission

Failed the Nation and Why.

University Press of Kansas.

ISBN�978-0-7006-1390-8.

- Newman, John (1995).

Oswald and the CIA.

Carroll & Graf Publishers.

ISBN�978-0-7867-0131-5.

- Rappleye, Charles; Ed

Becker (1991). All American Mafioso.

Doubleday.

ISBN�978-0-385-26676-5.

- Summers, Anthony (1998).

Not in Your Lifetime: The Definitive Book on the JFK

Assassination. Marlowe & Company.

ISBN�978-1-56924-739-6.

-

Almog, Oz,

Kosher Nostra J�dische Gangster in Amerika,

1890�1980�; J�dischen Museum der Stadt Wien�; 2003, Text

Oz Almog, Erich Metz,

ISBN 3901398333

External

links

SOURCE:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Ruby |