PATRICE LUMUMBATHE BULLET RIDDEN BODY OF PRESIDENT

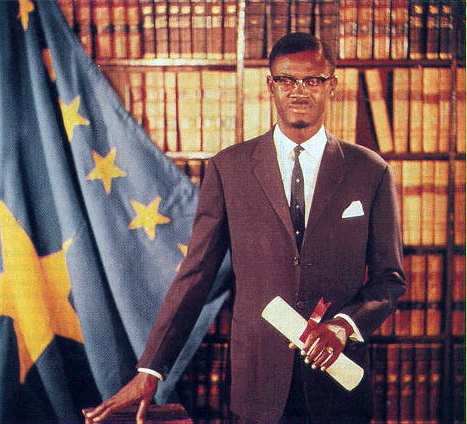

PATRICE LUMUMBA Patrice Émery Lumumba (2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese independence leader and the first legally elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo after he helped win its independence from Belgium in June 1960. Only ten weeks later, Lumumba's government was deposed in a coup during the Congo Crisis.[1] He was subsequently imprisoned and murdered in circumstances suggesting the support and complicity of the governments of Belgium and the United States.[2][3] Path to Prime MinisterEarly life and careerLumumba was born in Onalua in the Katakokombe region of the Kasai province of the Belgian Congo, a member of the Tetela ethnic group. Raised in a Catholic family as one of four sons, he was educated at a Protestant primary school, a Catholic missionary school, and finally the government post office training school, passing the one-year course with distinction. He subsequently worked in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) and Stanleyville (now Kisangani) as a postal clerk and as a travelling beer salesman. In 1951, he married Pauline Opangu. In 1955, Lumumba became regional head of the Cercles of Stanleyville and joined the Liberal Party of Belgium, where he worked on editing and distributing party literature. After traveling on a three-week study tour in Belgium, he was arrested in 1955 on charges of embezzlement of post office funds. His two-year sentence was commuted to twelve months after it was confirmed by Belgian lawyer Jules Chrome that Lumumba had returned the funds, and he was released in July 1956. After his release, he helped found the broad-based Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) in 1958, later becoming the organization's president. Lumumba and his team represented the MNC at the All-African Peoples' Conference in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958. At this international conference, hosted by influential Pan-African President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Lumumba further solidified his Pan-Africanist beliefs. Leader of MNCIn late October 1959, Lumumba as leader of the MNC was again arrested for allegedly inciting an anti-colonial riot in Stanleyville where thirty people were killed, for which he was sentenced to six months in prison. The trial's start date of 18 January 1960, was also the first day of a round-table conference in Brussels to finalize the future of the Congo. Despite Lumumba's imprisonment at the time, the MNC won a convincing majority in the December local elections in the Congo. As a result of pressure from delegates who were enraged at Lumumba's imprisonment, he was released and allowed to attend the Brussels conference. The conference culminated on January 27 with a declaration of Congolese independence setting June 30, 1960, as the independence date with national elections from 11–25 May 1960. Lumumba and the MNC won this election and the right to form a government, with the announcement on 23 June 1960 of 34-year-old Lumumba as Congo's first prime minister and Joseph Kasa-Vubu as its president. In accordance with the constitution, on 24 June the new government passed a vote of confidence and was ratified by the Congolese Chamber and Senate. Independence Day was celebrated on June 30 in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries including King Baudouin and the foreign press. Lumumba delivered his famous independence speech after being officially excluded from the event programme, despite being the new prime minister.[4] The speech of Belgian King Baudouin praised developments under colonialism, his reference to the "genius" of his great-granduncle Leopold II of Belgium glossing over atrocities committed during the Congo Free State.[2] The King continued, "Don't compromise the future with hasty reforms, and don't replace the structures that Belgium hands over to you until you are sure you can do better... Don't be afraid to come to us. We will remain by your side, give you advice."[5] Lumumba responded by reminding the audience that the independence of the Congo was not granted magnanimously by Belgium:[5]

In contrast to the relatively harmless speech of President Kasa-Vubu, Lumumba's reference to the suffering of the Congolese under Belgian colonialism stirred the crowd while simultaneously humiliating and alienating the King and his entourage. Some media claimed at the time that he ended his speech by ad-libbing, Nous ne sommes plus vos macaques! (We are no longer your monkeys!) --referring to a common slur used against Africans by Belgians, however, these words are neither in his written text nor in radio tapes of his speech.[2][6] Lumumba was later harshly criticised for what many in the Western world—but virtually none in Africa—described as the inappropriate nature of his speech.[7] Actions as Prime MinisterA few days after Congo gained its independence, Lumumba made the fateful decision to raise the pay of all government employees except for the army. Many units of the army also had strong objections toward the uniformly Belgian officers; General Janssens, the army head, told them their lot would not change after independence, and they rebelled in protest. The rebellions quickly spread throughout the country, leading to a general breakdown in law and order. Although the trouble was highly localized, the country seemed to be overrun by gangs of soldiers and looters, causing a media sensation, particularly over Europeans fleeing the country.[8] The province of Katanga declared independence under regional premier Moïse Tshombe on 11 July 1960 with support from the Belgian government and mining companies such as Union Minière.[9] Despite the arrival of UN troops, unrest continued. Since the United Nations refused to help suppress the rebellion in Katanga, Lumumba sought Soviet aid in the form of arms, food, medical supplies, trucks, and planes to help move troops to Katanga. Lumumba's decisive actions alarmed his colleagues and President Kasa-Vubu, who preferred a more moderate political approach.[10] Assassination

Deposition and arrestIn September, the President dismissed Lumumba from government. Lumumba immediately protested the legality of the President's actions. In retaliation, Lumumba declared Kasa-Vubu deposed and won a vote of confidence in the Senate, while the newly appointed prime minister failed to gain parliament's confidence. The country was torn by two political groups claiming legal power over the country. On 14 September, a coup d’état organised by Colonel Joseph Mobutu and endorsed by the Central Intelligence Agency incapacitated both Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu.[8] Lumumba was placed under house arrest at the prime minister's residence, although UN troops were positioned around the house to protect him. Nevertheless, Lumumba decided to rouse his supporters in Haut-Congo. Smuggled out of his residence at night, he escaped to Stanleyville, where he attempted to set up his own government and army.[12] Pursued by troops loyal to Mobutu he was finally captured in Port Francqui on 1 December 1960 and flown to Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) in handcuffs. He desperately appealed to local UN troops to save him, but he was no longer their responsibility[citation needed]. Mobutu said Lumumba would be tried for inciting the army to rebellion and other crimes. United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld made an appeal to Kasa-Vubu asking that Lumumba be treated according to due process of law. The USSR denounced Hammarskjöld and the Western powers as responsible for Lumumba's arrest and demanded his release. UN responseThe UN Security Council was called into session on 7 December 1960 to consider Soviet demands that the UN seek Lumumba's immediate release, the immediate restoration of Lumumba as head of the Congo government, the disarming of the forces of Mobutu, and the immediate evacuation of Belgians from the Congo. Hammarskjöld, answering Soviet attacks against his Congo operations, said that if the UN forces were withdrawn from the Congo "I fear everything will crumble." The threat to the UN cause was intensified by the announcement of the withdrawal of their contingents by Yugoslavia, the United Arab Republic, Ceylon, Indonesia, Morocco, and Guinea. The Soviet pro-Lumumba resolution was defeated on 14 December 1960 by a vote of 8-2. On the same day, a Western resolution that would have given Hammarskjöld increased powers to deal with the Congo situation was vetoed by the Soviet Union. Final daysLumumba was sent first on 3 December, to Thysville military barracks Camp Hardy, 150 km (about 100 miles) from Leopoldville. However, when security and disciplinary breaches threatened his safety, it was decided that he should be transferred to the Katanga Province. Lumumba was forcibly restrained on the flight to Elizabethville (now Lubumbashi) on 17 January 1961.[13] On arrival, he was conducted under arrest to Brouwez House and held there bound and gagged while President Tshombe and his cabinet decided what to do with him. Death by firing squadLater that night, Lumumba was driven to an isolated spot where three firing squads had been assembled. According to David Akerman, Ludo de Witte and Kris Hollington,[14] the firing squads were commanded by a Belgian, Captain Julien Gat, and another Belgian, Police Commissioner Verscheure, had overall command of the execution site.[15] The Belgian Commission has found that the execution was carried out by Katanga's authorities, but de Witte found written orders from the Belgian government requesting Lumumba's murder and documents on various arrangements, such as death squads. It reported that President Tshombe and two other ministers were present with four Belgian officers under the command of Katangan authorities. Lumumba and two other comrades from the government, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, were lined up against a tree and shot one at a time. The execution probably took place on 17 January 1961 between 21:40 and 21:43 according to the Belgian report. Lumumba's corpse was buried nearby. No statement was released until three weeks later despite rumours that Lumumba was dead. Announcement of deathHis death was formally announced on Katangese radio when it was alleged that he escaped and was killed by enraged villagers. On January 18, panicked by reports that the burial of the three bodies had been observed, members of the execution team went to dig up the bodies and move them to a place near the border with Rhodesia for reburial. Belgian Police Commissioner Gerard Soete later admitted in several accounts that he and his brother led the first and a second exhumation. Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure also took part. On the afternoon and evening of January 21, Commissioner Soete and his brother dug up Lumumba's corpse for the second time, cut it up with a hacksaw, and dissolved it in concentrated sulfuric acid (de Witte 2002:140-143).[16] Only some teeth and a fragment of skull and bullets survived the process, kept as souvenirs. In an interview on Belgian television in a program on the assassination of Lumumba in 1999, Soete displayed a bullet and two teeth that he boasted he had saved from Lumumba's body.[16] De Witte also mentions that Verscheure kept souvenirs from the exhumation: bullets from the skull of Lumumba.[17] After the announcement of Lumumba's death, street protests were organised in several European countries; in Belgrade, capital of Yugoslavia, protesters sacked the Belgian embassy and confronted the police, and in London a crowd marched from Trafalgar Square to the Belgian embassy, where a letter of protest was delivered and where protesters clashed with police.[18] American and Belgian involvement"Lumumba’s pan-Africanism and his vision of a united Congo gained him many enemies. Both Belgium and the United States actively sought to have him killed. The CIA ordered his assassination but could not complete the job. Instead, the United States and Belgium covertly funneled cash and aid to rival politicians who seized power and arrested Lumumba."[19] U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had said "something [to CIA chief Allen Dulles] to the effect that Lumumba should be eliminated".[20] This was revealed by a declassified interview with then-US National Security Council minutekeeper Robert Johnson released in August 2000 from Senate intelligence committee's inquiry on covert action. The committee later found that while the CIA had conspired to kill Lumumba, it was not directly involved in the actual murder.[20] Church CommitteeIn 1975, the Church Committee went on record with the finding that Allen Dulles had ordered Lumumba's assassination as "an urgent and prime objective" (Dulles' own words).[21] Furthermore, declassified CIA cables quoted or mentioned in the Church report and in Kalb (1972) mention two specific CIA plots to murder Lumumba: the poison plot and a shooting plot. Although some sources claim that CIA plots ended when Lumumba was captured, that is not stated or shown in the CIA records. Rather, those records show two still-partly-censored CIA cables from Elizabethville on days significant in the murder: January 17, the day Lumumba died, and January 18, the day of the first exhumation. The former, after a long censored section, talks about where they need to go from there. The latter expresses thanks for Lumumba being sent to them and then says that, had Elizabethville base known he was coming, they would have "baked a snake".[22] Significantly, a CIA officer told another CIA officer later that he had had Lumumba's body in the trunk of his car to try to find a way to dispose of it.[23] This cable goes on to state that the writer's sources (not yet declassified) said that after being taken from the airport Lumumba was imprisoned by "all white guards".[24] Belgian investigationThe Belgian Commission investigating Lumumba's assassination concluded that (1) Belgium wanted Lumumba arrested, (2) Belgium was not particularly concerned with Lumumba's physical well being, and (3) although informed of the danger to Lumumba's life, Belgium did not take any action to avert his death, but the report also specifically denied that Belgium ordered Lumumba's assassination.[25] Under its own 'Good Samaritan' laws, Belgium was legally culpable for failing to prevent the assassination from taking place and was also in breach of its obligation (under U.N. Resolution 290 of 1949) to refrain from acts or threats "aimed at impairing the freedom, independence or integrity of another state."[26] The report of 2001 by the Belgian Commission mentions that there had been previous U.S. and Belgian plots to kill Lumumba. Among them was a Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored attempt to poison him, which may have come on orders from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[27] CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb was a key person in this by devising a poison resembling toothpaste.[28][29][30][31] However, the plan is said to have been scrapped because the local CIA Station Chief, Larry Devlin, refused permission.[29][30][32] However, as Kalb points out in her book, Congo Cables, the record shows that many communications by Devlin at the time urged elimination of Lumumba (p. 53, 101, 129-133, 149-152, 158-159, 184-185, 195). Also, the CIA station chief helped to direct the search to capture Lumumba for his transfer to his enemies in Katanga, was involved in arranging his transfer to Katanga (p. 158, Hoyt, Michael P. 2009, "Captive in the Congo: A Consul's Return to the Heart of Darkness"), and the CIA base chief in Elizabethville was in direct touch with the killers the night Lumumba was killed. Furthermore, a CIA agent had the body in the trunk of his car in order to try to get rid of it (p. 105, Stockwell, John 1978 In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story. Stockwell, who knew Devlin well, felt Devlin knew more than anyone else about the murder (71-72, 136-137). Belgian apologyIn February 2002, the Belgian government apologised to the Congolese people, and admitted to a "moral responsibility" and "an irrefutable portion of responsibility in the events that led to the death of Lumumba." U.S. documentsIn July 2006, documents released by the United States government revealed that the CIA had plotted to assassinate Lumumba. In September 1960, Sidney Gottlieb brought a vial of poison to the Congo with plans to place it on Lumumba's toothbrush. The plot was later abandoned. It is currently unknown the extent to which the CIA was involved in his eventual death.[29] This same disclosure showed that U.S. perception at the time was that Lumumba was a communist.[33] Eisenhower's reported call, at a meeting of his national security advisers, for Lumumba's elimination must have been brought on by this perception. Both Belgium and the US were clearly influenced in their unfavourable stance towards Lumumba by the Cold War. He seemed to gravitate around the Soviet Union, although this was not because he was a communist but the only place he could find support in his country's effort to rid itself of colonial rule.[34] The US was the first country from which Lumumba requested help.[35] Lumumba, for his part, not only denied being a Communist, but said he found colonialism and Communism to be equally deplorable, and professed his personal preference for neutrality between the East and West.[36] Legacy

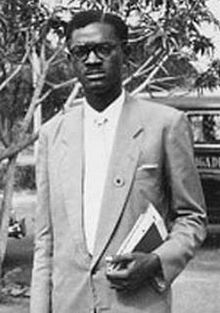

"Today, it is impossible to touch down at the

(far from modernized)

airport of

Lubumbashi in the south of the Democratic

Republic of Congo without a shiver of

recollection of the haunting photograph taken of

Lumumba there shortly before his assassination,

and after beatings, torture and a long, long

flight in custody across the vast country which

had so loved him."

— Victoria Brittain,

The Guardian, 2011

[11]

PoliticalThe results of his time in office are both mixed and polarising in their subsequent interpretation. To his critics, Lumumba bequeathed very few positive results from his term of office. Their critiques include his inability to promote development and failure to stave off or quell a civil war that erupted within days of his appointment as prime minister. Instead, he behaved impetuously and followed expedients rather than policies that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, including himself.[38] To his supporters, Lumumba was an altruistic man of strong character who pursued his policies regardless of opposing viewpoints. He favoured a unitary Congo and opposed division of the country along ethnic or regional lines.[39][40] Like many other African leaders, he supported pan-Africanism and liberation for colonial territories.[41] He proclaimed his regime one of "positive neutralism,"[42] defined as a return to African values and rejection of any imported ideology, including that of the Soviet Union: "We are not Communists, Catholics, Socialists. We are African nationalists."[43] 2006 Congolese electionsNevertheless, the image of Patrice Lumumba continues to serve as an inspiration in contemporary Congolese politics. In the 2006 elections, several parties claimed to be motivated by his ideas, including the People's Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD), the political party initiated by the incumbent President Joseph Kabila.[44] Antoine Gizenga, who served as Lumumba's Deputy Prime Minister in the post-independence period, was a 2006 Presidential candidate under the Unified Lumumbist Party (Parti Lumumbiste Unifié (PALU))[45] and was named prime minister at the end of the year. Other political parties that directly utilise his name include the Mouvement National Congolais-Lumumba (MNC-L) and the Mouvement Lumumbiste (MLP). Family and politicsPatrice Lumumba's family is actively involved in contemporary Congolese politics. Patrice Lumumba was married to Pauline Lumumba and had five children; François was the eldest followed by Patrice Junior, Julienne, Roland and Guy-Patrice Lumumba. François was 10 years old when Patrice died. Before his imprisonment, Patrice arranged for his wife and children to move into exile in Egypt, where François spent his childhood, then went to Hungary for education (he holds a doctorate in political economics). He returned to Congo in 1992 to oppose Mobutu since which time he has been the leader of the Mouvement National Congolais Lumumba (MNC-L), his father's original political party.[46] Lumumba's youngest son, Guy-Patrice, born six months after his father's death, was an independent presidential candidate in the 2006 elections,[47] but received less than 10% of the vote. Tributes

USSR commemorative stamp, 1961

BibliographyWritings by Lumumba

Writings about Lumumba

Films

Archive video and audio

Other

References

External links

|