Allende's involvement in Chilean political life spanned a period of nearly forty years. As a member of the Socialist Party, he was a senator, deputy and cabinet minister. He unsuccessfully ran for the presidency in the 1952, 1958, and 1964 elections. In 1970, he won the presidency in a close three-way race.

He adopted the policy of nationalization of industries and collectivization. Amidst strikes by the far-right Patria y Libertad and CIA opposition under the Nixon administration, protests were held in Chile against Allende's rule.[2] The Supreme Court criticized Allende for subordination of the judicial system to serve his own political needs; and the Chamber of Deputies formally implored the military to intercede and restore rule of law on August 22, 1973. Less than a month later, on September 11, Allende was deposed[3] by the military, thus ending the Popular Unity government.[4][5] As the armed forces surrounded La Moneda Palace, Allende gave his last speech vowing not to resign,[6] but he was said by the U.S. to have committed suicide later in the day.[7] Shortly following Allende's ouster, General Augusto Pinochet refrained from returning authority to the civilian government, and Chile became led by a junta.

In late January 2011, a Chilean judge ordered an inquiry into Allende's death.[8]

Early life

Allende was born on June 26, 1908 in Valpara�so.[9] He was the son of Salvador Allende Castro and Laura Gossens Uribe. Allende's family belonged to the Chilean upper-class and had a long tradition of political involvement in progressive and liberal causes. His grandfather was a prominent physician and a social reformist who founded one of the first secular schools in Chile.[10] Salvador Allende was of Belgian and Basque[11] descent.

Allende attended high school at the Liceo Eduardo de la Barra in Valpara�so. As a teenager, his main intellectual and political influence came from the shoe-maker Juan De Marchi, an Italian-born anarchist.[10] Allende was a talented athlete in his youth, being a member of the Everton de Vi�a del Mar sports club (named after the more famous English football club of the same name and which regularly competes at the highest level in Chilean football), where he is said to have excelled at the long jump.[12] Allende then graduated with a medical degree in 1926 at the University of Chile.[10]

He co-founded section Socialist Party of Chile (founded in 1933 with Marmaduque Grove and others) in Valpara�so[10] and became its chairman. He married Hortensia Bussi with whom he had three daughters. In 1933, he published his doctoral thesis Higiene Mental y Delincuencia (Crime and Mental Hygiene) in which he criticized Cesare Lombroso's proposals.[13]

In 1938, Allende was in charge of the electoral campaign of the Popular Front headed by Pedro Aguirre Cerda.[10] The Popular Front's slogan was "Bread, a Roof and Work!"[10] After its electoral victory, he became Minister of Health in the Reformist Popular Front government which was dominated by the Radicals.[10] Entering the government, he relinquished his parliamentary seat for Valpara�so, which he had won in 1937. Around that time, he wrote La Realidad M�dico Social de Chile (The social and medical reality of Chile). After the Kristallnacht in Nazi Germany, Allende and other members of the Parliament sent a telegram to Adolf Hitler denouncing the persecution of Jews.[14] Following Aguirre's death in 1941, he was again elected deputy while the Popular Front was re-named Democratic Alliance.

In 1945, Allende became senator for the Valdivia, Llanquihue, Chilo�, Ais�n and Magallanes provinces; then for Tarapac� and Antofagasta in 1953; for Aconcagua and Valpara�so in 1961; and once more for Chilo�, Ais�n and Magallanes in 1969. He became president of the Chilean Senate in 1966.

His three unsuccessful bids for the presidency (in the 1952, 1958 and 1964 elections) prompted Allende to joke that his epitaph would be "Here lies the next President of Chile." In 1952, as candidate for the Frente de Acci�n Popular (Popular Action Front, FRAP), he obtained only 5.4% of the votes, partly due to a division within socialist ranks over support for Carlos Ib��ez. In 1958, again as the FRAP candidate, Allende obtained 28.5% of the vote. This time, his defeat was attributed to votes lost to the populist Antonio Zamorano.[15] In 1964, once more as the FRAP candidate, he lost again, polling 38.6% of the votes against 55.6% for Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. As it became clear that the election would be a race between Allende and Frei, the political right � which initially had backed Radical Julio Dur�n.[16] � settled for Frei as "the lesser evil". Allende's socialist beliefs and friendship with Cuban president Fidel Castro made him deeply unpopular within the administrations of successive U.S. presidents, from John F. Kennedy to Richard Nixon; they believed there was a danger of Chile becoming a communist state and joining the Soviet Union's sphere of influence. Allende, however, publicly condemned the Soviet invasion of Hungary (1956) and of Czechoslovakia[17] (1968) and he later made Chile the first Government in continental America to recognize the People's Republic of China (1971).

Relationship with the Chilean Communist Party

Allende had a close relationship with the Chilean Communist Party from the beginning of his political career. On his fourth (and successful) bid for the presidency, the Communist Party appointed him as the alternate for its own candidate, the world-renowned poet Pablo Neruda.

During his presidential term, Allende took positions held by the communists, in opposition to the views of the socialists. Some argue, however, that this was reversed at the end of his period in office.[18]

Election

Allende won the 1970 Chilean presidential election as leader of the Unidad Popular ("Popular Unity") coalition. On September 4, 1970, he obtained a narrow plurality of 36.2 percent to 34.9 percent over Jorge Alessandri, a former president, with 27.8 percent going to a third candidate (Radomiro Tomic) of the Christian Democratic Party (PDC), whose electoral platform was similar to Allende's. According to the Chilean Constitution of the time, if no presidential candidate obtained a majority of the popular vote, Congress would choose one of the two candidates with the highest number of votes as the winner. Tradition was for Congress to vote for the candidate with the highest popular vote, regardless of margin. Indeed, former president Jorge Alessandri had been elected in 1958 with only 31.6 percent of the popular vote, defeating Allende.

One month after the election, on October 20, while the senate had still to reach a decision and negotiations were actively in place between the Christian Democrats and the Popular Unity, General Ren� Schneider, Commander in Chief of the Chilean Army, was shot resisting a kidnap attempt by a group led by General Roberto Viaux. Hospitalized, he died of his wounds three days later, on October 23. Viaux's kidnapping plan had been supported by the CIA, although the then U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger claims to have ordered the plans postponed at the last moment. Many believe Kissinger's statement to be false and evidence points towards CIA director Richard Helms following orders directly from President Nixon to do whatever was necessary in order �to get rid of him�, referring to Allende. Nixon handed over a blank check to Helms, which allowed him to use full discretion in ridding Chile of Allende�s presence and �making the economy scream�. Schneider was a defender of the "constitutionalist" doctrine that the army's role is exclusively professional, its mission being to protect the country's sovereignty and not to interfere in politics.

General Schneider's death was widely disapproved of and, for the time, ended military opposition to Allende,[19] whom the parliament finally chose on October 24. On October 26, President Eduardo Frei named General Carlos Prats as commander in chief of the army to replace Ren� Schneider.

Allende assumed the presidency on November 3, 1970 after signing a Statute of Constitutional Guarantees proposed by the Christian Democrats in return for their support in Congress. In an extensive interview with R�gis Debray in 1972, Allende explained his reasons for agreeing to the guarantees.[20] Some critics have interpreted Allende's responses as an admission that signing the Statute was only a tactical move.[21]

Presidency

Upon assuming power, Allende began to carry out his platform of implementing a socialist program called La v�a chilena al socialismo ("the Chilean Path to Socialism"). This included nationalization of large-scale industries (notably copper mining and banking), and government administration of the health care system, educational system (with the help of an American educator, Jane A. Hobson-Gonzalez from Kokomo, Indiana), a program of free milk for children in the schools and shanty towns of Chile, and an expansion of the land seizure and redistribution already begun under his predecessor Eduardo Frei Montalva,[22] who had nationalized between one-fifth and one-quarter of all the properties listed for takeover.[23] The Allende government's intention was to seize all holdings of more than eighty irrigated hectares.[24] Allende also intended to improve the socio-economic welfare of Chile's poorest citizens;[citation needed] a key element was to provide employment, either in the new nationalised enterprises or on public work projects.[citation needed]

The new Minister of Agriculture, Jacques Chonchol, promised to expropriate all estates which were larger than eighty �basic� hectares. This promise was kept, with no farm in Chile exceeding this limit by the end of 1972.[25]

The Allende Government also sought to bring the arts (both serious and popular) to the mass of the Chilean population by funding a number of cultural endeavors. With eighteen-year olds and illiterates now granted the right to vote, mass participation in decision-making was encouraged by the Allende government, with traditional hierarchical structures now challenged by socialist egalitarianism. The Allende Government was also able to draw upon the idealism of its supporters, with teams of Allendistas travelling into the countryside and shanty towns to perform volunteer work.[26]

Social spending was dramatically increased, particularly for housing, education, and health, while a major effort was made to redistribute wealth to poorer Chileans. As a result of new initiatives in nutrition and health, together with higher wages, many poorer Chileans were able to feed themselves and clothe themselves better than they had been able to before. Public access to the social security system was increased, while state benefits such as family allowances were raised significantly.[27]

Chilean presidents were allowed a maximum term of six years, which may explain Allende's haste to restructure the economy. Not only was a major restructuring program organized (the Vuskovic plan), he had to make it a success if a Socialist successor to Allende was going to be elected. In the first year of Allende's term, the short-term economic results of Minister of the Economy Pedro Vuskovic's expansive monetary policy were highly favorable: 12% industrial growth and an 8.6% increase in GDP, accompanied by major declines in inflation (down from 34.9% to 22.1%) and unemployment (down to 3.8%). However by 1972, the Chilean escudo had an inflation rate of 140%. The average Real GDP contracted between 1971 and 1973 at an annual rate of 5.6% ("negative growth"); and the government's fiscal deficit soared while foreign reserves declined [Flores, 1997: source requires title/publisher]. The combination of inflation and government-mandated price-fixing, together with the "disappearance" of basic commodities from supermarket shelves, led to the rise of black markets in rice, beans, sugar, and flour.[28] The Chilean economy also suffered as a result of a US campaign against the Allende government.[29] The Allende government announced it would default on debts owed to international creditors and foreign governments. Allende also froze all prices while raising salaries. His implementation of these policies was strongly opposed by landowners, employers, businessmen and transporters associations, and some civil servants and professional unions. The rightist opposition was led by National Party, the Roman Catholic Church (which in 1973 was displeased with the direction of educational policy),[30] and eventually the Christian Democrats. There were growing tensions with foreign multinational corporations and the government of the United States.

Allende also undertook Project Cybersyn, a system of networked telex machines and computers. Cybersyn was developed by British cybernetics expert Stafford Beer. The network transmitted data from factories to the government in Santiago, allowing for economic planning in real-time.[31]

In 1971, Chile re-established diplomatic relations with Cuba, joining Mexico and Canada in rejecting a previously-established Organization of American States convention prohibiting governments in the Western Hemisphere from establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba. Shortly afterward, Cuban president Fidel Castro made a month-long visit to Chile. Originally the visit was supposed to be one week, however Castro enjoyed Chile, and one week turned to another. The visit, in which Castro held massive rallies and gave public advice to Allende, was seen by those on the political right as proof to support their view that "The Chilean Path to Socialism" was an effort to put Chile on the same path as Cuba.[citation needed] Castro after his visit drew the conclusion; Cuba has nothing to learn from Chile.[citation needed]

October 1972 saw the first of what were to be a wave of strikes. The strikes were led first by truckers, and later by small businessmen, some (mostly professional) unions and some student groups. Other than the inevitable damage to the economy, the chief effect of the 24-day strike was to induce Allende to bring the head of the army, general Carlos Prats, into the government as Interior Minister.[28] Allende also instructed the government to begin requisitioning trucks in order to keep the nation from coming to a halt. Government supporters also helped to mobilize trucks and buses but violence served as a deterrent to full mobilization, even with police protection for the strike breakers. Allende's actions were eventually declared unlawful by the Chilean appeals court and the government was ordered to return trucks to their owners.[32]

Throughout this presidency racial tensions between the poor descendants of indigenous people , who supported Allende's reforms, and the white settler elite increased.[33]

Allende raised wages on a number of occasions throughout 1970 and 1971, but these wage hikes were negated by the in-tandem inflation of Chile's fiat currency. Although price rises had also been high under Frei (27% a year between 1967 and 1970), a basic basket of consumer goods rose by 120% from 190 to 421 escudos in one month alone, August 1972. In the period 1970-72, while Allende was in government, exports fell 24% and imports rose 26%, with imports of food rising an estimated 149%.[34]

Export income fell due to a hard hit copper industry: the price of copper on international markets fell by almost a third, and post-nationalization copper production fell as well. Copper is Chile's single most important export (more than half of Chile's export receipts were from this sole commodity[35]). The price of copper fell from a peak of $66 per ton in 1970 to only $48�9 in 1971 and 1972.[36] Chile was already dependent on food imports, and this decline in export earnings coincided with declines in domestic food production following Allende's agrarian reforms.[37]

Throughout his presidency, Allende remained at odds with the Chilean Congress, which was dominated by the Christian Democratic Party. The Christian Democrats (who had campaigned on a socialist platform in the 1970 elections, but drifted away from those positions during Allende's presidency, eventually forming a coalition with the National Party), continued to accuse Allende of leading Chile toward a Cuban-style dictatorship, and sought to overturn many of his more radical policies. Allende and his opponents in Congress repeatedly accused each other of undermining the Chilean Constitution and acting undemocratically.

Allende's increasingly bold socialist policies (partly in response to pressure from some of the more radical members within his coalition), combined with his close contacts with Cuba, heightened fears in Washington. The Nixon administration began exerting economic pressure on Chile via multilateral organizations, and continued to back Allende's opponents in the Chilean Congress. Almost immediately after his election, Nixon directed CIA and U.S. State Department officials to "put pressure" on the Allende government.[38]

Foreign relations during Allende's presidency

Allende's Popular Unity government tried to maintain normal relations with the United States. When Chile nationalized its copper industry, Washington cut off U.S. credits and increased its support to opposition. Forced to seek alternative sources of trade and finance, Chile gained commitments from the Soviet Union to invest some $400 million in Chile in the next six years. Allende's government was disappointed that it received far less economic assistance from the USSR than it hoped for. Trade between the two countries did not significantly increase and the credits were mainly linked to the purchase of Soviet equipment. Moreover, credits from the Soviet Union were much less than those provided by the People's Republic of China and countries of Eastern Europe. When Allende visited the USSR in late 1972 in search of more aid and additional lines of credit, after 3 years of political and economic failure and chaos he was turned down.[39]

Foreign involvement in Chile during Allende's Presidency

US involvement

The possibility of Allende winning Chile's 1970 election was deemed a disaster by a US government who wanted to protect US business interests and prevent any spread of communism during the Cold War.[40] In September 1970, President Nixon informed the CIA that an Allende government in Chile would not be acceptable and authorized $10 million to stop Allende from coming to power or unseat him.[41] The CIA's plans to impede Allende's investiture as President of Chile were known as "Track I" and "Track II"; Track I sought to prevent Allende from assuming power via so-called "parliamentary trickery", while under the Track II initiative, the CIA tried to convince key Chilean military officers to carry out a coup.[41]

During Nixon's presidency, U.S. officials attempted to prevent Allende's election by financing political parties aligned with opposition candidate Jorge Alessandri and supporting strikes in the mining and transportation sectors.[42]

After the 1970 election, the Track I operation attempted to incite Chile's outgoing president, Eduardo Frei Montalva, to persuade his party (PDC) to vote in Congress for Alessandri.[citation needed] Under the plan, Alessandri would resign his office immediately after assuming it and call new elections. Eduardo Frei would then be constitutionally able to run again (since the Chilean Constitution did not allow a president to hold two consecutive terms, but allowed multiple non-consecutive ones), and presumably easily defeat Allende. The Chilean Congress instead chose Allende as President, on the condition that he would sign a "Statute of Constitutional Guarantees" affirming that he would respect and obey the Chilean Constitution, and that his reforms would not undermine any element of it.

Track II was aborted, as parallel initiatives already underway within the Chilean military rendered it moot.[43]

The United States has acknowledged having played a role in Chilean politics prior to the coup, but its degree of involvement in the coup itself is debated. The CIA was notified by its Chilean contacts of the impending coup two days in advance, but contends it "played no direct role in" the coup.[44]

Much of the internal opposition to Allende's policies came from business sector, and recently-released U.S. government documents confirm that the U.S. indirectly [29] funded the truck drivers' strike,[45] which exacerbated the already chaotic economic situation prior to the coup.

The most prominent U.S. corporations in Chile prior to Allende's presidency were the Anaconda and Kennecott Copper companies, and ITT Corporation, International Telephone and Telegraph. Both the copper corporations aimed to expand privatized copper production in the city of El Teniente, Chile, the world's largest underground copper mine.[46] At the end of 1968, according to Department of Commerce data, U.S. corporate holdings in Chile amounted to $964 million. Anaconda and Kennecott accounted for 28% of U.S. holdings, but ITT had by far the largest holding of any single corporation, with an investment of $200 million in Chile.[46] In 1970, before Allende was elected, ITT owned 70% of Chitelco, the Chilean Telephone Company and funded El Mercurio, a Chilean right-wing newspaper. Documents released in 2000 by the CIA confirmed that before the elections of 1970, ITT gave $700,000 to Allende's conservative opponent, Jorge Alessandri, with help from the CIA on how to channel the money safely. ITT president Harold Geneen also offered $1 million to the CIA to help defeat Allende in the elections.[47]

After General Pinochet assumed power, United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told President Richard Nixon that the U.S. "didn't do it," but "we helped them...created the conditions as great as possible." (referring to the coup itself).[48] Recent documents declassified under the Clinton administration's Chile Declassification Project show that the United States government and the CIA sought the overthrow of Allende in 1970 immediately before he took office ("Project FUBELT"). Many documents regarding the 1973 coup remain classified.

Soviet involvement

Material based on reports from the Mitrokhin Archive, the KGB said of Allende that "he was made to understand the necessity of reorganising Chile's army and intelligence services, and of setting up a relationship between Chile's and the USSR's intelligence services". It is also claimed that Allende was given $30,000 "in order to solidify the trusted relations" with him.[49] According to Vasili Mitrokhin, a former KGB major and senior archivist in the KGB intelligence central of Yasenevo, Allende made a personal request for Soviet money through his personal contact, KGB officer Svyatoslav Kuznetsov, who urgently came to Chile from Mexico City to help Allende.[50] The original allocation of money for these elections through the KGB was $400,000, and an additional personal subsidy of $50,000 was sent directly to Allende.[50]

Historian Christopher Andrew argued that help from the KGB was a decisive factor, because Allende won by a narrow margin of 39,000 votes of a total of the 3 million cast. After the elections, the KGB director Yuri Andropov obtained permission for additional money and other resources from the Central Committee of the CPSU to ensure an Allende victory in Congress. In his request on October 24, he stated that the KGB "will carry out measures designed to promote the consolidation of Allende's victory and his election to the post of President of the country". In his KGB file, Allende was reported to have "stated his willingness to co-operate on a confidential basis and provide any necessary assistance, since he considered himself a friend of the Soviet Union". He willingly shared political information.[50]

Andrew writes that regular Soviet contact with Allende after his election was maintained by his KGB case officer, Svyatoslav Kuznetsov, who was instructed by the centre to "exert a favorable influence on Chilean government policy". Allende was said to have reacted favorably.

Political and moral support came mostly through the Communist Party and unions. For instance, he received the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union in 1972. However, there were some fundamental differences between Allende and Soviet political analysts who believed that some violence � or measures that those analysts "theoretically considered to be just" � should have been used.[51] According to Andrew's account of the Mitrokhin archives, "In the KGB's view, Allende's fundamental error was his unwillingness to use force against his opponents. Without establishing complete control over all the machinery of the State, his hold on power could not be secure."[49]

Declarations from KGB General Nikolai Leonov, former Deputy Chief of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB, confirmed that the Soviet Union supported Allende's government economically, politically and militarily.[51] Leonov stated in an interview at the Chilean Center of Public Studies (CEP) that the Soviet economic support included over $100 million in credit, three fishing ships (that distributed 17,000 tons of frozen fish to the population), factories (as help after the 1971 earthquake), 3,100 tractors, 74,000 tons of wheat and more than a million tins of condensed milk.[51]

In mid-1973 the USSR had approved the delivery of weapons (artillery, tanks) to the Chilean Army. However, when news of an attempt from the Army to depose Allende through a coup d'�tat reached Soviet officials, the shipment was redirected to another country.[51]

Crisis

On June 29, 1973, Colonel Roberto Souper surrounded the La Moneda presidential with his tank regiment and failed to depose the Allende Government.[52] That failed coup d��tat � known as the Tanquetazo tank putsch � organised by the nationalist Patria y Libertad paramilitary group, was followed by a general strike at the end of July that included the copper miners of El Teniente.

In August 1973, a constitutional crisis occurred, and the Supreme Court publicly complained about the Allende Government's inability to enforce the law of the land, and, on August 22, the Chamber of Deputies (with the Christian Democrats united with the National Party) accused Allende`s Government of unconstitutional acts by his refusal to promulgate constitutional amendments already approved by the chamber of deputies that prevented his government from continuing his massive statization plan[53] and called upon the military to enforce constitutional order.[54]

For months, the Allende Government had feared calling upon the Carabineros (Carabineers) national police, suspecting them disloyal to his government. On August 9, President Allende appointed Gen. Carlos Prats as Minister of Defense. On August 24, 1973, General Prats was forced to resign both as defense minister and as the Army Commander-in-chief, embarrassed by both the Alejandrina Cox incident and a public protest in front of his house by the wives of his generals. Gen. Augusto Pinochet replaced him as Army commander-in-chief the same day.[54]

Supreme Court's resolution

On May 26, 1973, Chile�s Supreme Court unanimously denounced the Allende government's disruption of the legality of the nation in its failure to uphold judicial decisions, because of its continual refusal to permit police execution of judicial resolutions contradicting the Government's measures.

Chamber of Deputies' resolution

On August 22, 1973 the Christian Democrats and the National Party members of the Chamber of Deputies voted 81 to 47, a resolution that asked the authorities[55] to put an immediate end to breach[es of] the Constitution . . . with the goal of redirecting government activity toward the path of Law and ensuring the Constitutional order of our Nation, and the essential underpinnings of democratic co-existence among Chileans.

The resolution declared that the Allende Government sought . . . to conquer absolute power with the obvious purpose of subjecting all citizens to the strictest political and economic control by the State . . . [with] the goal of establishing a totalitarian system, claiming it had made violations of the Constitution . . . a permanent system of conduct. Essentially, most of the accusations were about the Socialist Government disregarding the separation of powers, and arrogating legislative and judicial prerogatives to the executive branch of government.

Specifically, the Socialist Government of President Allende was accused of:

- Ruling by decree, thwarting the normal legislative system

- Refusing to enforce judicial decisions against its partisans; not carrying out sentences and judicial resolutions that contravene its objectives

- Ignoring the decrees of the independent General Comptroller's Office

- Sundry media offenses; usurping control of the National Television Network and applying ... economic pressure against those media organizations that are not unconditional supporters of the government...

- Allowing its socialist supporters to assemble armed, preventing the same by its right wing opponents

- Supporting more than 1,500 illegal �takings� of farms...

- Illegal repression of the El Teniente miners� strike

- Illegally limiting emigration

Finally, the resolution condemned the creation and development of government-protected [socialist] armed groups, which . . . are headed towards a confrontation with the armed forces. President Allende's efforts to re-organize the military and the police forces were characterized as notorious attempts to use the armed and police forces for partisan ends, destroy their institutional hierarchy, and politically infiltrate their ranks.[56]

President Allende's response

Two days later, on August 24, 1973, President Allende responded,[57] characterising the Congress's declaration as destined to damage the country�s prestige abroad and create internal confusion, predicting It will facilitate the seditious intention of certain sectors. He noted that the declaration (passed 81-47 in the Chamber of Deputies) had not obtained the two-thirds Senate majority constitutionally required to convict the president of abuse of power: essentially, the Congress were invoking the intervention of the armed forces and of Order against a democratically-elected government and subordinat[ing] political representation of national sovereignty to the armed institutions, which neither can nor ought to assume either political functions or the representation of the popular will.

Mr Allende argued he had obeyed constitutional means for including military men to the cabinet at the service of civic peace and national security, defending republican institutions against insurrection and terrorism. In contrast, he said that Congress was promoting a coup d��tat or a civil war with a declaration full of affirmations that had already been refuted beforehand and which, in substance and process (directly handing it to the ministers rather than directly handing it to the President) violated a dozen articles of the (then-current) Constitution. He further argued that the legislature was usurping the government's executive function.

President Allende wrote: Chilean democracy is a conquest by all of the people. It is neither the work nor the gift of the exploiting classes, and it will be defended by those who, with sacrifices accumulated over generations, have imposed it . . . With a tranquil conscience . . . I sustain that never before has Chile had a more democratic government than that over which I have the honor to preside . . . I solemnly reiterate my decision to develop democracy and a state of law to their ultimate consequences . . . Parliament has made itself a bastion against the transformations . . . and has done everything it can to perturb the functioning of the finances and of the institutions, sterilizing all creative initiatives.

Adding that economic and political means would be needed to relieve the country's current crisis, and that the Congress were obstructing said means; having already paralyzed the State, they sought to destroy it. He concluded by calling upon the workers, all democrats and patriots to join him in defending the Chilean Constitution and the revolutionary process.

The coup

In early September 1973, Allende floated the idea of resolving the constitutional crisis with a plebiscite. His speech outlining such a solution was scheduled for September 11, but he was never able to deliver it. On September 11, 1973, the Chilean military staged a coup against Allende.

Death

Just prior to the capture of La Moneda (the Presidential Palace), with gunfire and explosions clearly audible in the background, Allende gave his (subsequently famous) farewell speech to Chileans on live radio, speaking of himself in the past tense, of his love for Chile and of his deep faith in its future. He stated that his commitment to Chile did not allow him to take an easy way out, and he would not be used as a propaganda tool by those he called "traitors" (he refused an offer of safe passage), clearly implying he intended to fight to the end.[58]

| "Workers of my country, I have faith in Chile and its destiny. Other men will overcome this dark and bitter moment when treason seeks to prevail. Keep in mind that, much sooner than later, the great avenues will again be opened through which will pass free men to construct a better society. Long live Chile! Long live the people! Long live the workers!" |

| President Salvador Allende's farewell speech, September 11, 1973.[6] |

Shortly afterwards, it is believed Allende committed suicide. An official announcement declared that he had committed suicide with an automatic rifle. In his 2004 documentary Salvador Allende, Patricio Guzm�n incorporates a graphic image of Allende's corpse in the position it was found after his death. According to Guzm�n's documentary, Allende shot himself with a pistol and not a rifle.

Initially, there was some confusion over the cause of Allende's death. In recent years the view that he committed suicide has become accepted, particularly as different testimonies confirm details of the suicide reported in news and documentary interviews.[59][60][61][62][63] His personal doctor described the death as a suicide, and his family accepts the finding. The notion that he was assassinated persists and is referenced in the Michael Moore film Bowling for Columbine.[64]

Family

|

|

This section requires expansion. |

Likely the best-known relative of Salvador Allende is Isabel Allende, author of novels such as The House of Spirits, and daughter of his first cousin Tom�s Allende, a Chilean diplomat.

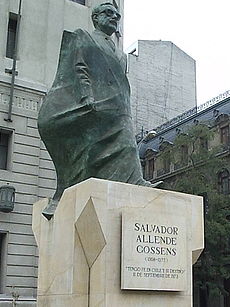

Memorials to Allende include a statue in front of the Palacio de la Moneda.

Allende in popular culture

Although still a controversial figure, Allende was chosen in 2008 as the Greatest Chilean in history by a competition on national public television, winning over other important national figures such as Arturo Prat, Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral.[65]

See also

References

|

|

Constructs such as ibid. and loc. cit. are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. |

- ^ "Profile of Salvador Allende". BBC.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2003). Communism: A History. The Modern Library. p. 137. ISBN 0812968646.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2003). Communism: A History. The Modern Library. p. 138. ISBN 0812968646.

- ^ "The Christian Science monitor: Controversial legacy of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet ....Gen. Augusto Pinochet, who overthrew Chile's democratically elected Communist government in a 1973 coup ...".

- ^ "Chile: The Bloody End of a Marxist Dream... Allende's downfall had implications that reached far beyond the borders of Chile. His had been the first democratically elected Marxist government in Latin America...". Time Magazine.

- ^ a b Salvador Allende's Last Speech

- ^ Labarca, Eduardo (2007) Salvador Allende, biograf�a sentimental, Catalonia, pp.339-405 ISBN 978-956-8303-68-6

- ^ "Chilean Judge Orders Investigation Into Allende�s Death". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ^ "Biography of Allende". salvador-allende.cl.

- ^ a b c d e f g Patricio Guzm�n, Salvador Allende (film documentary, 2004)

- ^ "?".[dead link]

- ^ Tallentire, Mark (August 3, 2010). "A hundred years on, Everton face Everton for the first time". The Guardian (London).

- ^ "Unmasked defamatory libel on Salvador Allende". May 27, 2005. with link to thesis, on the Clarin's website (English) (Spanish version available)

- ^ "Telegram protesting against the persecution of Jews in Germany". El Clar�n de Chile's. (Spanish)

- ^ "Translation".

- ^ "Translation".

- ^ ?.[dead link]

- ^ Gonzalo Rojas Sanchez; Columna Centenaria, 2008.

- ^ Mark Falcoff (November 10, 2003). "Kissinger and Chile originally". frontpagemag.com. Retrieved September 21, 2006.

- ^ R�gis Debray (1972). The Chilean Revolution: Conversations with Allende. New York: Vintage Books.

- ^ "Como Allende destruyo la democracia en Chile". elcato.org. (Spanish)

- ^ (Spanish) "La Unidad Popular". icarito.latercera.cl. Archived from the original on 2005-03-07., archived March 7, 2005 on the Internet Archive

- ^ Collier & Sater, 1996.

- ^ Faundez, 1988.

- ^ A History of Chile, 1808-1994, by Simon Collier and William F. Sater

- ^ ibid

- ^ ibid

- ^ a b (Spanish) "Comienzan los problemas". Enciclopedia Escolar Icarito. Archived from the original on 2003-09-22.. Archived on the Internet Archive, September 22, 2003

- ^ a b United States Senate Report (1975) "Covert Action in Chile, 1963-1973" U.S. Government Printing Office Washington. D.C.

- ^ (Spanish) "Declaraci�n de la Asamblea Plenaria del Episcopado sobre la Escuela Nacional Unificada". Conferencia Episcopal de Chile. April 11, 1973.

- ^ Eden Medina, "Designing Freedom, Regulating a Nation: Socialist Cybernetics in Allende's Chile," Journal of Latin American Studies 38 (2006):571-606.

- ^ Edy Kaufman, "Crisis in Allende's Chile: New Perspectives", Praeger Publishers, New York, 1988. 266-267.

- ^ Richard Gott.Latin America is preparing to settle accounts with its white settler elite. Guardian Unlimited, November 15, 2006. Retrieved on December 22, 2006.

- ^ Figures are from November, 1986, pp. 4-12, tables 1.1 & 1.7

- ^ Hoogvelt, 1997

- ^ Nove, 1986

- ^ Tier, Mark, 1973, "Allende Erred", Nation Review (Melbourne, Australia), October 12�18

- ^ Still Hidden: A Full Record Of What the U.S. Did in Chile, Peter Kornbluh, The Washington Post, Sunday October 24, 1999; Page B01

- ^ The USSR and Latin America By Eusebio Mujal-Le�n

- ^ "Pawn or Player? Chile in the cold war".

- ^ a b Hinchey Report CIA Activities in Chile. September 18, 2000. Accessed online November 18, 2006.

- ^ CIA Reveals Covert Acts In Chile, Admits Support For Kidnappers, Links To Pinochet Regime - CBS News

- ^ "Church Report. Covert Action in Chile 1963-1973", December 18, 1975.

- ^ CIA Reveals Covert Acts In Chile, CBS News, September 19, 2000.

- ^ Jonathan Franklin, Files show Chilean blood on US hands, The Guardian, October 11, 1999.

- ^ a b Moran, Theodore (1974). Multinational Corporations and the Politics of Dependence: Copper in Chile. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Daniel Brandt, U.S. Responsibility for the Coup in Chile, Namebase, November 28, 1988.

- ^ "The Kissinger Telcons: Kissinger Telcons on Chile, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 123, edited by Peter Kornbluh, posted May 26, 2004". This particular dialogue can be found at "Telcon: September 16, 1973, 11:50 a.m. Kissinger Talking to Nixon". Retrieved November 26, 2006..

- ^ a b Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin How 'weak' Allende was left out in the cold by the KGB (excerpt from The Mitrokhin Archive Volume II), The Times (UK), September 19, 2005.

- ^ a b c The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World by Christopher Andrew, 736 pages, 2005.

- ^ a b c d "Soviet intelligence in Latin America during the Cold War - Lectures by General Nikolai Leonov". Centro de Estudios Publicos (Chile). September 22, 1999..

- ^ Second coup attempt: El Tanquetazo (the tank attack), originally on RebelYouth.ca. Unsigned, but with citations. Archived on Internet Archive October 13, 2004.

- ^ Historia de Chile. Accessed online May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b (Spanish) Se desata la crisis, part of series "Icarito > Enciclopedia Virtual > Historia > Historia de Chile > Del gobierno militar a la democracia" on LaTercera.cl. Accessed September 22, 2006.

- ^ "The President of the Republic, Ministers of State, and members of the Armed and Police Forces".

- ^ English translation on Wikisource.

- ^ (Spanish) respuesta del Presidente Allende on Wikisource. (English) English translation on Wikisource, accessed September 22, 2006.

- ^ "Socialist Says AllendeOnce Spoke of Suicide". The New York Times. September 12, 1973. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ "The World: Allende's Last Day". Time. February 4, 1974. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ Christian, Shirley (September 17, 1990). "Leftist Journal Concludes Allende Killed Himself". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ^ "Wife admits Allende suicide with gun Castro gave him". Chicago Tribune. September 16, 1973.

- ^ Parkinson, William (September 16, 1973). "The death of Allende: Officially a suicide". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Camus, Ignacio Gonzalez, El dia en que murio Allende ("The day that Allende Died"). Instituto Chileno de Estudios Human�sticos (ICHEH) and Centro de Estudios Sociales (CESOC), 1988. p. 282 and following.

- ^ "Profile: Salvador Allende". BBC News. 2009-09-08. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ "Allende es el gran chileno".

Other sources

- Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents relating to the Military Coup, 1970-1976, (From the United States' National Security Archive).

- Thomas Karamessines (1970). Operation Guide for the Conspiration in Chile, Washington: United States National Security Council.

- Isabel Allende, Chilean writer, Allende's niece.

- Henry A. Kissinger

- La Batalla de Chile) � Cuba/Chile/Fran�a/Venezuela, 1975, 1977 e 1979. Director Patricio Guzm�n. Duration: 272 minutes. (Spanish)

- M�rquez, Gabriel Garc�a. Chile, el golpe y los gringos. Cr�nica de una tragedia organizada, Man�gua, Nicaragua: Radio La Primeirissima, 11 de setembro de 2006 (Spanish)

- Kornbluh, Peter. El Mercurio file, The., Columbia Journalism Review, Sep/Oct 2003

- Victoria A. Schobert-Gonzalez, Jane A. Gonzalez's American daughter-in-law, Writer, Historian, Artist, Naturalist

External links

- Photos of the public places named in homage to the President Allende all around the world

- Salvador Allende's "Last Words" Spanish text with English translation. The transcript of the last radio broadcast of Chilean President Salvador Allende, made on September 11, 1973, at 9:10 am. MP3 audio available here.

- Caso Pinochet. While nominally a page about the Pinochet case, this large collection of links includes Allende's dissertation and numerous documents (mostly PDFs) related to the dissertation and to the controversy about it, ranging from the Cesare Lombroso material discussed in Allende's dissertation to a collective telegram of protest over Kristallnacht signed by Allende. (Spanish)

- An Interview with Salvadore Allende: President of Chile, interviewed by Saul Landau, Dove Films, 1971, 32 min. (previously unreleased):

- Video (Spanish with English subtitles) in El Clarin de Chile. (Alternative location at Google Video

- September 11, 1973, When US-Backed Pinochet Forces Took Power in Chile - video report by Democracy Now!