|

An Act of State: The Execution of Martin

Luther King An Act of

State: The Execution of Martin Luther

King

�In 1977 the family of Martin Luther

King engaged an attorney and friend, Dr.

William Pepper, to investigate a

suspicion they had. They no longer

believed that James Earl Ray was the

killer. For their peace of mind, for an

accurate record of history, and out of a

sense of justice they conducted a two

decade long investigation. The evidence

they uncovered was put before a jury in

Memphis, TN, in November 1999. 70

witnesses testified under oath, 4,000

pages of transcripts described that

evidence, much of it new. It took the

jury 59 minutes to come back with their

decision that exonerated James Earl Ray,

who had already died in prison. The jury

found that Lloyd Jowers, owner of Jim�s

Grill, had participated in a conspiracy

to kill King. The evidence showed that

the conspiracy included J. Edgar Hoover

and the FBI, Richard Helms and the CIA,

the military, the Memphis police

department, and organized crime.�

http://actofstate.org/

HOW

UNITED STATES INTELLIGENCE

ASSASSINATED MARTIN LUTHER KING JR

(

PDF |

ASCII text formats )

The following appeared

in the May-June 2000 issue of

Probe

magazine, (Vol.7,No.4) and is mirrored

from

http://ctka.net/pr500-king.html with

permission of the author. We are

grateful for Jim Douglass' "being there"

and for his penetrating exploration and

accounting of the 20th Century's true

"trial of the century".

|

The

Martin

Luther

King

Conspiracy

|

|

Exposed

in

Memphis

|

|

by Jim

Douglass

|

|

Spring

2000

|

|

Probe

Magazine

|

|

|

|

According to a Memphis

jury's verdict on December

8, 1999, in the wrongful

death lawsuit of the King

family versus Loyd Jowers

"and other unknown

co-conspirators," Dr. Martin

Luther King Jr. was

assassinated by a conspiracy

that included agencies of

his own government. Almost

32 years after King's murder

at the Lorraine Motel in

Memphis on April 4, 1968, a

court extended the circle of

responsibility for the

assassination beyond the

late scapegoat James Earl

Ray to the United States

government.

I can hardly believe the

fact that, apart from the

courtroom participants, only

Memphis TV reporter Wendell

Stacy and I attended from

beginning to end this

historic three-and-one-half

week trial. Because of

journalistic neglect

scarcely anyone else in this

land of ours even knows what

went on in it. After

critical testimony was given

in the trial's second week

before an almost empty

gallery, Barbara Reis, U.S.

correspondent for the Lisbon

daily Publico who was

there several days, turned

to me and said, "Everything

in the U.S. is the trial of

the century. O.J. Simpson's

trial was the trial of the

century. Clinton's trial was

the trial of the century.

But this is the trial

of the century, and who's

here?"

What I experienced in that

courtroom ranged from

inspiration at the courage

of the Kings, their

lawyer-investigator William

F. Pepper, and the

witnesses, to amazement at

the government's carefully

interwoven plot to kill Dr.

King. The seriousness with

which U.S. intelligence

agencies planned the murder

of Martin Luther King Jr.

speaks eloquently of the

threat Kingian nonviolence

represented to the powers

that be in the spring of

1968.

In the complaint filed by

the King family, "King

versus Jowers and Other

Unknown Co-Conspirators,"

the only named defendant,

Loyd Jowers, was never their

primary concern. As soon

became evident in court, the

real defendants were the

anonymous co-conspirators

who stood in the shadows

behind Jowers, the former

owner of a Memphis bar and

grill. The Kings and Pepper

were in effect charging U.S.

intelligence agencies --

particularly the FBI and

Army intelligence -- with

organizing, subcontracting,

and covering up the

assassination. Such a charge

guarantees almost

insuperable obstacles to its

being argued in a court

within the United States.

Judicially it is an

unwelcome beast.

|

I can

hardly believe the fact

that, apart from the

courtroom participants,

only Memphis TV reporter

Wendell Stacy and I

attended from beginning

to end this historic

three-and-one-half week

trial. Because of

journalistic neglect

scarcely anyone else in

this land of ours even

knows what went on in

it. After critical

testimony was given in

the trial's second week

before an almost empty

gallery, Barbara Reis,

U.S. correspondent for

the Lisbon daily

Publico who was

there several days,

turned to me and said,

"Everything in the U.S.

is the trial of the

century. O.J. Simpson's

trial was the trial of

the century. Clinton's

trial was the trial of

the century. But this

is the trial of the

century, and who's

here?" |

Many qualifiers have been attached to the

verdict in the King case. It

came not in criminal court

but in civil court, where

the standards of evidence

are much lower than in

criminal court. (For

example, the plaintiffs used

unsworn testimony made on

audiotapes and videotapes.)

Furthermore, the King family

as plaintiffs and Jowers as

defendant agreed ahead of

time on much of the

evidence.

But these observations are

not entirely to the point.

Because of the government's

"sovereign immunity," it is

not possible to put a U.S.

intelligence agency in the

dock of a U.S. criminal

court. Such a step would

require authorization by the

federal government, which is

not likely to indict itself.

Thanks to the conjunction of

a civil court, an

independent judge with a

sense of history, and a

courageous family and

lawyer, a spiritual

breakthrough to an

unspeakable truth occurred

in Memphis. It allowed at

least a few people (and

hopefully many more through

them) to see the forces

behind King's martyrdom and

to feel the responsibility

we all share for it through

our government. In the end,

twelve jurors, six black and

six white, said to everyone

willing to hear: guilty as

charged.

We can also thank the

unlikely figure of Loyd

Jowers for providing a way

into that truth.

Loyd Jowers: When the frail,

73-year-old Jowers became

ill after three days in

court, Judge Swearengen

excused him. Jowers did not

testify and said through his

attorney, Lewis Garrison,

that he would plead the

Fifth Amendment if

subpoenaed. His discretion

was too late. In 1993

against the advice of

Garrison, Jowers had gone

public. Prompted by William

Pepper's progress as James

Earl Ray's attorney in

uncovering Jowers's role in

the assassination, Jowers

told his story to Sam

Donaldson on Prime Time

Live. He said he had

been asked to help in the

murder of King and was told

there would be a decoy (Ray)

in the plot. He was also

told that the police

"wouldn't be there that

night."

In that interview, the

transcript of which was read

to the jury in the Memphis

courtroom, Jowers said the

man who asked him to help in

the murder was a

Mafia-connected produce

dealer named Frank Liberto.

Liberto, now deceased, had a

courier deliver $100,000 for

Jowers to hold at his

restaurant, Jim's Grill, the

back door of which opened

onto the dense bushes across

from the Lorraine Motel.

Jowers said he was visited

the day before the murder by

a man named Raul, who

brought a rifle in a box.

As Mike Vinson reported in

the March-April Probe,

other witnesses testified to

their knowledge of Liberto's

involvement in King's

slaying. Store-owner John

McFerren said he arrived

around 5:15 pm, April 4,

1968, for a produce pick-up

at Frank Liberto's warehouse

in Memphis. (King would be

shot at 6:0l pm.) When he

approached the warehouse

office, McFerren overheard

Liberto on the phone inside

saying, "Shoot the

son-of-a-bitch on the

balcony."

Caf�-owner Lavada Addison, a

friend of Liberto's in the

late 1970's, testified that

Liberto had told her he "had

Martin Luther King killed."

Addison's son, Nathan

Whitlock, said when he

learned of this conversation

he asked Liberto point-blank

if he had killed King.

"[Liberto] said, `I didn't

kill the nigger but I had it

done.' I said, `What about

that other son-of-a-bitch

taking credit for it?' He

says, `Ahh, he wasn't

nothing but a troublemaker

from Missouri. He was a

front man . . . a setup

man.'"

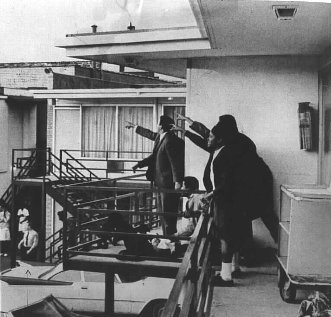

The jury also heard a tape

recording of a two-hour-long

confession Jowers made at a

fall 1998 meeting with

Martin Luther King's son

Dexter and former UN

Ambassador Andrew Young. On

the tape Jowers says that

meetings to plan the

assassination occurred at

Jim's Grill. He said the

planners included undercover

Memphis Police Department

officer Marrell McCollough

(who now works for the

Central Intelligence Agency,

and who is referenced in the

trial transcript as Merrell

McCullough), MPD Lieutentant

Earl Clark (who died in

1987), a third police

officer, and two men Jowers

did not know but thought

were federal agents.

Young, who witnessed the

assassination, can be heard

on the tape identifying

McCollough as the man

kneeling beside King's body

on the balcony in a famous

photograph. According to

witness Colby Vernon Smith,

McCollough had infiltrated a

Memphis community organizing

group, the Invaders, which

was working with the

Southern Christian

Leadership Conference. In

his trial testimony Young

said the MPD intelligence

agent was "the guy who ran

up [the balcony stairs] with

us to see Martin."

Jowers says on the tape that

right after the shot was

fired he received a smoking

rifle at the rear door of

Jim's Grill from Clark. He

broke the rifle down into

two pieces and wrapped it in

a tablecloth. Raul picked it

up the next day. Jowers said

he didn't actually see who

fired the shot that killed

King, but thought it was

Clark, the MPD's best

marksman.

Young testified that his

impression from the 1998

meeting was that the aging,

ailing Jowers "wanted to get

right with God before he

died, wanted to confess it

and be free of it." Jowers

denied, however, that he

knew the plot's purpose was

to kill King -- a claim that

seemed implausible to Dexter

King and Young. Jowers has

continued to fear jail, and

he had directed Garrison to

defend him on the grounds

that he didn't know the

target of the plot was King.

But his interview with

Donaldson suggests he was

not na�ve on this point.

Loyd Jowers's story opened

the door to testimony that

explored the systemic nature

of the murder in seven other

basic areas:

-

background to the

assassination;

-

local conspiracy;

-

the crime scene;

-

the rifle;

-

Raul;

-

broader conspiracy;

-

cover-up.

- Background to the

assassination

James Lawson, King's

friend and an organizer

with SCLC, testified

that King's stands on

Vietnam and the Poor

People's Campaign had

created enemies in

Washington. He said

King's speech at New

York's Riverside Church

on April 4, 1967, which

condemned the Vietnam

War and identified the

U.S. government as "the

greatest purveyor of

violence in the world

today," provoked intense

hostility in the White

House and FBI.

Hatred and fear of King

deepened, Lawson said,

in response to his plan

to hold the Poor

People's Campaign in

Washington, D.C. King

wanted to shut down the

nation's capital in the

spring of 1968 through

massive civil

disobedience until the

government agreed to

abolish poverty. King

saw the Memphis

sanitation workers'

strike as the beginning

of a nonviolent

revolution that would

redistribute income.

"I have no doubt,"

Lawson said, "that the

government viewed all

this seriously enough to

plan his assassination."

Coretta Scott King

testified that her

husband had to return to

Memphis in early April

1968 because of a

violent demonstration

there for which he had

been blamed. Moments

after King arrived in

Memphis to join the

sanitation workers'

march there on March 28,

1968, the scene turned

violent -- subverted by

government provocateurs,

Lawson said. Thus King

had to return to Memphis

on April 3 and prepare

for a truly nonviolent

march, Mrs. King said,

to prove SCLC could

still carry out a

nonviolent campaign in

Washington.

- Local conspiracy

On the night of April 3,

1968, Floyd E. Newsum, a

black firefighter and

civil rights activist,

heard King's "I've Been

to the Mountain Top"

speech at the Mason

Temple in Memphis. On

his return home, Newsum

returned a phone call

from his lieutenant and

was told he had been

temporarily transferred,

effective April 4, from

Fire Station 2, located

across the street from

the Lorraine Motel, to

Fire Station 31. Newsum

testified that he was

not needed at the new

station. However, he was

needed at his old

station because his

departure left it "out

of service unless

somebody else was

detailed to my company

in my stead." After

making many queries,

Newsum was eventually

told he had been

transferred by request

of the police

department.

The only other black

firefighter at Fire

Station 2, Norvell E.

Wallace, testified that

he, too, received orders

from his superior

officer on the night of

April 3 for a temporary

transfer to a fire

station far removed from

the Lorraine Motel. He

was later told vaguely

that he had been

threatened.

Wallace guessed it was

because "I was putting

out fires," he told the

jury with a smile. Asked

if he ever received a

satisfactory explanation

for his transfer Wallace

answered, "No. Never

did. Not to this day."

In the March-April

Probe, Mike Vinson

described the similar

removal of Ed Redditt, a

black Memphis Police

Department detective,

from his Fire Station 2

surveillance post two

hours before King's

murder.

To understand the

Redditt incident, it is

important to note that

it was Redditt himself

who initiated his watch

on Dr. King from the

firehouse across the

street. Redditt

testified that when

King's party and the

police accompanying them

(including Detective

Redditt) arrived from

the airport at the

Lorraine Motel on April

3, he "noticed something

that was unusual." When

Inspector Don Smith, who

was in charge of

security, told Redditt

he could leave, Redditt

"noticed there was

nobody else there. In

the past when we were

assigned to Dr. King

[when Redditt had been

part of a black security

team for King], we

stayed with him. I saw

nobody with him. So I

went across the street

and asked the Fire

Department could we come

in and observe from the

rear, which we did."

Given Redditt's concerns

for King's safety, his

particular watch on the

Lorraine may not have

fit into others' plans.

Redditt testified that

late in the afternoon of

April 4, MPD

Intelligence Officer Eli

Arkin came to Fire

Station 2 to take him to

Central Headquarters.

There Police and Fire

Director Frank Holloman

(formerly an FBI agent

for 25 years, seven of

them as supervisor of J.

Edgar Hoover's office)

ordered Redditt home,

against his wishes and

accompanied by Arkin.

The reason Holloman gave

Redditt for his removal

from the King watch

Redditt had initiated

the day before was that

his life had been

threatened.

In an interview after

the trial, Redditt told

me the story of how his

1978 testimony on this

question before the

House Select Committee

on Assassinations was

part of a heavily

pressured cover-up. "It

was a farce," he said,

"a total farce."

Redditt had been

subpoenaed by the HSCA

to testify, as he came

to realize, not so much

on his strange removal

from Fire Station 2 as

the fact that he had

spoken about it openly

to writers and

researchers. The HSCA

focused narrowly on the

discrepancy between

Redditt's surveiling

King (as he was doing)

and acting as security

(an impression Redditt

had given writers

interviewing him) in

order to discredit the

story of his removal.

Redditt was first

grilled by the committee

for eight straight hours

in a closed executive

session. After a day of

hostile questioning,

Redditt finally said

late in the afternoon,

"I came here as a friend

of the investigation,

not as an enemy of the

investigation. You don't

want to deal with the

truth." He told the

committee angrily that

if the secret purpose

behind the King

conspiracy was, like the

JFK conspiracy, "to

protect the country,

just tell the American

people! They'll be

happy! And quit fooling

the folks and trying to

pull the wool over their

eyes."

When the closed hearing

was over, Redditt

received a warning call

from a friend in the

White House who said,

"Man, your life isn't

worth a wooden nickel."

Redditt said his public

testimony the next day

"was a set-up": "The

bottom line on that one

was that Senator Baker

decided that I wouldn't

go into this open

hearing without an

attorney. When the

lawyer and I arrived at

the hearing, we were

ushered right back out

across town to the

executive director in

charge of the

investigation. [We]

looked through a book,

to look at the questions

and answers."

"So in essence what they

were saying was: `This

is what you're going to

answer to, and this is

how you're going to

answer.' It was all made

up -- all designed,

questions and answers,

what to say and what not

to say. A total farce."

Former MPD Captain Jerry

Williams followed

Redditt to the witness

stand. Williams had been

responsible for forming

a special security unit

of black officers

whenever King came to

Memphis (the unit

Redditt had served on

earlier). Williams took

pride in providing the

best possible protection

for Dr. King, which

included, he said,

advising him never to

stay at the Lorraine

"because we couldn't

furnish proper security

there." ("It was just an

open view," he explained

to me later, "Anybody

could . . . There was no

protection at all. To me

that was a set-up from

the very beginning.")

|

Hatred

and fear of King

deepened, Lawson said,

in response to his plan

to hold the Poor

People's Campaign in

Washington, D.C. King

wanted to shut down the

nation's capital in the

spring of 1968 through

massive civil

disobedience until the

government agreed to

abolish poverty. King

saw the Memphis

sanitation workers'

strike as the beginning

of a nonviolent

revolution that would

redistribute income. "I

have no doubt," Lawson

said, "that the

government viewed all

this seriously enough to

plan his assassination."

|

For King's April 3, 1968

arrival, however,

Williams was for some

reason not asked to form

the special black

bodyguard. He was told

years later by his

inspector (a man whom

Jowers identified as a

participant in the

planning meetings at

Jim's Grill) that the

change occurred because

somebody in King's

entourage had asked

specifically for no

black security officers.

Williams told the jury

he was bothered by the

omission "even to this

day."

Leon Cohen, a retired

New York City police

officer, testified that

in 1968 he had become

friendly with the

Lorraine Motel's owner

and manager, Walter

Bailey (now deceased).

On the morning after

King's murder, Cohen

spoke with a visibly

upset Bailey outside his

office at the Lorraine.

Bailey told Cohen about

a strange request that

had forced him to change

King's room to the

location where he was

shot.

Bailey explained that

the night before King's

arrival he had received

a call "from a member of

Dr. King's group in

Atlanta." The caller

(whom Bailey said he

knew but referred to

only by the pronoun

"he") wanted the motel

owner to change King's

room. Bailey said he was

adamantly opposed to

moving King, as

instructed, from an

inner court room behind

the motel office (which

had better security) to

an outside balcony room

exposed to public view.

"If they had listened to

me," Bailey said, "this

wouldn't have happened."

Philip Melanson, author

of the Martin Luther

King Assassination

(1991), described his

investigation into the

April 4 pullback of four

tactical police units

that had been patrolling

the immediate vicinity

of the Lorraine Motel.

Melanson asked MPD

Inspector Sam Evans (now

deceased), commander of

the units, why they were

pulled back the morning

of April 4, in effect

making an assassin's

escape much easier.

Evans said he gave the

order at the request of

a local pastor connected

with King's party, Rev.

Samuel Kyles. (Melanson

wrote in his book that

Kyles emphatically

denied making any such

request.) Melanson said

the idea that MPD

security would be

determined at such a

time by a local pastor's

request made no sense

whatsoever.

Olivia Catling lived a

block away from the

Lorraine on Mulberry

Street. Catling had

planned to walk down the

street the evening of

April 4 in the hope of

catching a glimpse of

King at the motel. She

testified that when she

heard the shot a little

after six o'clock, she

said, "Oh, my God, Dr.

King is at that hotel!"

She ran with her two

children to the corner

of Mulberry and Huling

streets, just north of

the Lorraine. She saw a

man in a checkered shirt

come running out of the

alley beside a building

across from the

Lorraine. The man jumped

into a green 1965

Chevrolet just as a

police car drove up

behind him. He gunned

the Chevrolet around the

corner and up Mulberry

past Catling's house

moving her to exclaim,

"It's going to take us

six months to pay for

the rubber he's burning

up!!" The police, she

said, ignored the man

and blocked off a

street, leaving his car

free to go the opposite

way.

I visited Catling in her

home, and she told me

the man she had seen

running was not James

Earl Ray. "I will go

into my grave saying

that was not Ray,

because the gentleman I

saw was heavier than

Ray."

"The police," she told

me, "asked not one

neighbor [around the

Lorraine], `What did you

see?' Thirty-one years

went by. Nobody came and

asked one question. I

often thought about

that. I even had

nightmares over that,

because they never said

anything. How did they

let him get away?"

Catling also testified

that from her vantage

point on the corner of

Mulberry and Huling she

could see a fireman

standing alone across

from the motel when the

police drove up. She

heard him say to the

police, "The shot came

from that clump of

bushes," indicating the

heavily overgrown brushy

area facing the Lorraine

and adjacent to Fire

Station 2.

- The crime scene

Earl Caldwell was a

New York Times

reporter in his room at

the Lorraine Motel the

evening of April 4. In

videotaped testimony,

Caldwell said he heard

what he thought was a

bomb blast at 6:00 p.m.

When he ran to the door

and looked out, he saw a

man crouched in the

heavy part of the bushes

across the street. The

man was looking over at

the Lorraine's balcony.

Caldwell wrote an

article about the figure

in the bushes but was

never questioned about

what he had seen by any

authorities.

In a 1993 affidavit from

former SCLC official

James Orange that was

read into the record,

Orange said that on

April 4, "James Bevel

and I were driven around

by Marrell McCollough, a

person who at that time

we knew to be a member

of the Invaders, a local

community organizing

group, and who we

subsequently learned was

an undercover agent for

the Memphis Police

Department and who now

works for the Central

Intelligence Agency . .

. [After the shot, when

Orange saw Dr. King's

leg dangling over the

balcony], I looked back

and saw the smoke. It

couldn't have been more

than five to ten

seconds. The smoke came

out of the brush area on

the opposite side of the

street from the Lorraine

Motel. I saw it rise up

from the bushes over

there. From that day to

this time I have never

had any doubt that the

fatal shot, the bullet

which ended Dr. King's

life, was fired by a

sniper concealed in the

brush area behind the

derelict buildings.

"I also remember then

turning my attention

back to the balcony and

seeing Marrell

McCollough up on the

balcony kneeling over

Dr. King, looking as

though he was checking

Dr. King for life signs.

"I also noticed, quite

early the next morning

around 8 or 9 o'clock,

that all of the bushes

and brush on the hill

were cut down and

cleaned up. It was as

though the entire area

of the bushes from

behind the rooming house

had been cleared . . .

"I will always remember

the puff of white smoke

and the cut brush and

having never been given

a satisfactory

explanation.

"When I tried to tell

the police at the scene

as best I saw they told

me to be quiet and to

get out of the way.

"I was never interviewed

or asked what I saw by

any law enforcement

authority in all of the

time since 1968."

Also read into the

record were depositions

made by Solomon Jones to

the FBI and to the

Memphis police. Jones

was King's chauffeur in

Memphis. The FBI

document, dated April

13, 1968, says that

after King was shot,

when Jones looked across

Mulberry Street into the

brushy area, "he got a

quick glimpse of a

person with his back

toward Mulberry Street.

. . . This person was

moving rather fast, and

he recalls that he

believed he was wearing

some sort of

light-colored jacket

with some sort of a hood

or parka." In his 11:30

p.m., April 4, 1968

police interview, Jones

provides the same basic

information concerning a

person leaving the

brushy area hurriedly.

Maynard Stiles, who in

1968 was a senior

official in the Memphis

Sanitation Department,

confirmed in his

testimony that the

bushes near the rooming

house were cut down. At

about 7:00 a.m. on April

5, Stiles told the jury,

he received a call from

MPD Inspector Sam Evans

"requesting assistance

in clearing brush and

debris from a vacant lot

in the vicinity of the

assassination." Stiles

called another

superintendent of

sanitation, who

assembled a crew. "They

went to that site, and

under the direction of

the police department,

whoever was in charge

there, proceeded with

the clean-up in a slow,

methodical, meticulous

manner." Stiles

identified the site as

an area overgrown with

brush and bushes across

from the Lorraine Motel.

Within hours of King's

assassination, the crime

scene that witnesses

were identifying to the

Memphis police as a

cover for the shooter

had been sanitized by

orders of the police.

- The rifle

Probe readers

will again recall from

Mike Vinson's article

three key witnesses in

the Memphis trial who

offered evidence counter

to James Earl Ray's

rifle being the murder

weapon:

-

Judge Joe Brown;

-

Judge Arthur Hanes

Jr.;

-

William Hamblin.

-

Judge Joe Brown, who

had presided over

two years of

hearings on the

rifle, testified

that "67% of the

bullets from my

tests did not match

the Ray rifle." He

added that the

unfired bullets

found wrapped with

it in a blanket were

metallurgically

different from the

bullet taken from

King's body, and

therefore were from

a different lot of

ammunition. And

because the rifle's

scope had not been

sited, Brown said,

"this weapon

literally could not

have hit the broad

side of a barn."

Holding up the 30.06

Remington 760

Gamemaster rifle,

Judge Brown told the

jury, "It is my

opinion that this is

not the murder

weapon."

-

Circuit Court Judge

Arthur Hanes Jr. of

Birmingham, Alabama,

had been Ray's

attorney in 1968.

(On the eve of his

trial, Ray replaced

Hanes and his

father, Arthur Hanes

Sr., by Percy

Foreman, a decision

Ray told the Haneses

one week later was

the biggest mistake

of his life.) Hanes

testified that in

the summer of 1968

he interviewed Guy

Canipe, owner of the

Canipe Amusement

Company. Canipe was

a witness to the

dropping in his

doorway of a bundle

that held a trove of

James Earl Ray

memorabilia,

including the rifle,

unfired bullets, and

a radio with Ray's

prison

identification

number on it. This

dropped bundle,

heaven (or

otherwise) sent for

the State's case

against Ray, can be

accepted as credible

evidence through a

willing suspension

of disbelief. As

Judge Hanes

summarized the

State's

lone-assassin theory

(with reference to

an exhibit depicting

the scene), "James

Earl Ray had fired

the shot from the

bathroom on that

second floor, come

down that hallway

into his room and

carefully packed

that box, tied it

up, then had

proceeded across the

walkway the length

of the building to

the back where that

stair from that door

came up, had come

down the stairs out

the door, placed the

Browning box

containing the rifle

and the radio there

in the Canipe

entryway." Then Ray

presumably got in

his car seconds

before the police's

arrival, driving

from downtown

Memphis to Atlanta

unchallenged in his

white Mustang.

Concerning his

interview with the

witness who was the

cornerstone of this

theory, Judge Hanes

told the jury that

Guy Canipe (now

deceased) provided

"terrific evidence":

"He said that the

package was dropped

in his doorway by a

man headed south

down Main Street on

foot, and that this

happened at about

ten minutes before

the shot was

fired [emphasis

added]."

Hanes thought

Canipe's witnessing

the bundle-dropping

ten minutes before

the shot was very

credible for another

reason. It so

happened (as

confirmed by Philip

Melanson's research)

that at 6:00 p.m.

one of the MPD

tactical units that

had been withdrawn

earlier by Inspector

Evans, TACT 10, had

returned briefly to

the area with its 16

officers for a rest

break at Fire

Station 2. Thus, as

Hanes testified,

with the firehouse

brimming with

police, some already

watching King across

the street, "when

they saw Dr. King go

down, the fire house

erupted like a

beehive . . . In

addition to the time

involved [in Ray's

presumed odyssey

from the bathroom to

the car], it was

circumstantially

almost impossible to

believe that

somebody had been

able to throw that

[rifle] down and

leaave right in the

face of that

erupting fire

station."

When I spoke with

Judge Hanes after

the trial about the

startling evidence

he had received from

Canipe, he

commented, "That's

what I've been

saying for 30

years."

-

William Hamblin

testified not about

the rifle thrown

down in the Canipe

doorway but rather

the smoking rifle

Loyd Jowers said he

received at his back

door from Earl Clark

right after the

shooting. Hamblin

recounted a story he

was told many times

by his friend James

McCraw, who had

died.

James McCraw is

already well-known

to researchers as

the taxi driver who

arrived at the

rooming house to

pick up Charlie

Stephens shortly

before 6:00 p.m. on

April 4. In a

deposition read

earlier to the jury,

McCraw said he found

Stephens in his room

lying on his bed too

drunk to get up, so

McCraw turned out

the light and left

without him --

minutes before

Stephens, according

to the State,

identified Ray in

profile passing down

the hall from the

bathroom. McCraw

also said the

bathroom door next

to Stephen's room

was standing wide

open, and there was

no one in the

bathroom -- where

again, according to

the State, Ray was

then balancing on

the tub, about to

squeeze the trigger.

William Hamblin told

the jury that he and

fellow cab-driver

McCraw were close

friends for about 25

years. Hamblin said

he probably heard

McCraw tell the same

rifle story 50

times, but only when

McCraw had been

drinking and had his

defenses down.

In that story,

McCraw said that

Loyd Jowers had

given him the rifle

right after the

shooting. According

to Hamblin, "Jowers

told him to get the

[rifle] and get it

out of here now.

[McCraw] said that

he grabbed his beer

and snatched it out.

He had the rifle

rolled up in an oil

cloth, and he leapt

out the door and did

away with it."

McCraw told Hamblin

he threw the rifle

off a bridge into

the Mississippi

River.

Hamblin said McCraw

never revealed

publicly what he

knew of the rifle

because, like

Jowers, he was

afraid of being

indicted: "He really

wanted to come out

with it, but he was

involved in it. And

he couldn't really

tell the truth."

William Pepper

accepted Hamblin's

testimony about

McCraw's disposal of

the rifle over

Jowers's claim to

Dexter King that he

gave the rifle to

Raul. Pepper said in

his closing argument

that the actual

murder weapon had

been lying "at the

bottom of the

Mississippi River

for over thirty-one

years."

|

Maynard

Stiles, who in 1968 was

a senior official in the

Memphis Sanitation

Department, confirmed in

his testimony that the

bushes near the rooming

house were cut down. At

about 7:00 a.m. on April

5, Stiles told the jury,

he received a call from

MPD Inspector Sam Evans

"requesting assistance

in clearing brush and

debris from a vacant lot

in the vicinity of the

assassination. . . .

They went to that site,

and under the direction

of the police

department, whoever was

in charge there,

proceeded with the

clean-up in a slow,

methodical, meticulous

manner." . . . Within

hours of King's

assassination, the crime

scene that witnesses

were identifying to the

Memphis police as a

cover for the shooter

had been sanitized by

orders of the police.

|

- Raul

One of the most

significant developments

in the Memphis trial was

the emergence of the

mysterious Raul through

the testimony of a

series of witnesses.

In a 1995 deposition by

James Earl Ray that was

read to the jury, Ray

told of meeting Raul in

Montreal in the summer

of 1967, three months

after Ray had escaped

from a Missouri prison.

According to Ray, Raul

guided Ray's movements,

gave him money for the

Mustang car and the

rifle, and used both to

set him up in Memphis.

Andrew Young and Dexter

King described their

meeting with Jowers and

Pepper at which Pepper

had shown Jowers a

spread of photographs,

and Jowers picked out

one as the person named

Raul who brought him the

rifle to hold at Jim's

Grill. Pepper displayed

the same spread of

photos in court, and

Young and King pointed

out the photo Jowers had

identified as Raul.

(Private investigator

John Billings said in

separate testimony that

this picture was a

passport photograph from

1961, when Raul had

immigrated from Portugal

to the U.S.)

The additional witnesses

who identified the photo

as Raul's included:

British merchant seaman

Sidney Carthew, who in a

videotaped deposition

from England said he had

met Raul (who offered to

sell him guns) and a man

he thinks was Ray (who

wanted to be smuggled

onto his ship) in

Montreal in the summer

of 1967; Glenda and Roy

Grabow, who recognized

Raul as a gunrunner they

knew in Houston in the

`60s and `70s and who

told Glenda in a rage

that he had killed

Martin Luther King;

Royce Wilburn, Glenda's

brother, who also knew

Raul in Houston; and

British television

producer Jack Saltman,

who had obtained the

passport photo and

showed it to Ray in

prison, who identified

it as the photo of the

person who had guided

him.

Saltman and Pepper,

working on independent

investigations, located

Raul in 1995. He was

living quietly with his

family in the

northeastern U.S. It was

there in 1997 that

journalist Barbara Reis

of the Lisbon Publico,

working on a story about

Raul, spoke with a

member of his family.

Reis testified that she

had spoken in Portuguese

to a woman in Raul's

family who, after first

denying any connection

to Ray's Raul, said

"they" had visited them.

"Who?" Reis asked. "The

government," said the

woman. She said

government agents had

visited them three times

over a three-year

period. The government,

she said, was watching

over them and monitoring

their phone calls. The

woman took comfort and

satisfaction in the fact

that her family (so she

believed) was being

protected by the

government.

In his closing argument

Pepper said of Raul:

"Now, as I understand

it, the defense had

invited Raul to appear

here. He is outside this

jurisdiction, so a

subpoena would be

futile. But he was asked

to appear here. In

earlier proceedings

there were attempts to

depose him, and he

resisted them. So he has

not attempted to come

forward at all and tell

his side of the story or

to defend himself."

- A broader

conspiracy

Carthel Weeden, captain

of Fire Station 2 in

1968, testified that he

was on duty the morning

of April 4 when two U.S.

Army officers approached

him. The officers said

they wanted a lookout

for the Lorraine Motel.

Weeden said they carried

briefcases and indicated

they had cameras. Weeden

showed the officers to

the roof of the fire

station. He left them at

the edge of its

northeast corner behind

a parapet wall. From

there the Army officers

had a bird's-eye view of

Dr. King's balcony

doorway and could also

look down on the brushy

area adjacent to the

fire station.

The testimony of writer

Douglas Valentine filled

in the background of the

men Carthel Weeden had

taken up to the roof of

Fire Station 2. While

Valentine was

researching his book

The Phoenix Program

(1990), on the CIA's

notorious

counterintelligence

program against

Vietnamese villagers, he

talked with veterans in

military intelligence

who had been re-deployed

from the Vietnam War to

the sixties antiwar

movement. They told him

that in 1968 the Army's

111th Military

Intelligence Group kept

Martin Luther King under

24-hour-a-day

surveillance. Its agents

were in Memphis April 4.

As Valentine wrote in

The Phoenix Program,

they "reportedly watched

and took photos while

King's assassin moved

into position, took aim,

fired, and walked away."

Testimony which juror

David Morphy later

described as "awesome"

was that of former CIA

operative Jack Terrell,

a whistle-blower in the

Iran-Contra scandal.

Terrell, who was dying

of liver cancer in

Florida, testified by

videotape that his close

friend J.D. Hill had

confessed to him that he

had been a member of an

Army sniper team in

Memphis assigned to

shoot "an unknown

target" on April 4.

After training for a

triangular shooting, the

snipers were on their

way into Memphis to take

up positions in a

watertower and two

buildings when their

mission was suddenly

cancelled. Hill said he

realized, when he

learned of King's

assassination the next

day, that the team must

have been part of a

contingency plan to kill

King if another shooter

failed.

Terrell said J.D. Hill

was shot to death. His

wife was charged with

shooting Hill (in

response to his

drinking), but she was

not indicted. From the

details of Hill's death,

Terrell thought the

story about Hill's wife

shooting him was a

cover, and that his

friend had been

assassinated. In an

interview, Terrell said

the CIA's heavy

censorship of his book

Disposable Patriot

(1992) included

changing the paragraph

on J.D. Hill's death, so

that it read as if

Terrell thought Hill's

wife was responsible.

- Cover-up

Walter Fauntroy, Dr.

King's colleague and a

20-year member of

Congress, chaired the

subcommittee of the

1976-78 House Select

Committee on

Assassinations that

investigated King's

assassination. Fauntroy

testified in Memphis

that in the course of

the HSCA investigation

"it was apparent that we

were dealing with very

sophisticated forces."

He discovered electronic

bugs on his phone and TV

set. When Richard

Sprague, HSCA's first

chief investigator, said

he would make available

all CIA, FBI, and

military intelligence

records, he became a

focus of controversy.

Sprague was forced to

resign. His successor

made no demands on U.S.

intelligence agencies.

Such pressures

contributed to the

subcommittee's ending

its investigation, as

Fauntroy said, "without

having thoroughly

investigated all of the

evidence that was

apparent." Its formal

conclusion was that Ray

assassinated King, that

he probably had help,

and that the government

was not involved.

When I interviewed

Fauntroy in a van on his

way back to the Memphis

Airport, I asked about

the implications of his

statements in an April

4, 1997 Atlanta

Constitution

article. The article

said Fauntroy now

believed "Ray did not

fire the shot that

killed King and was part

of a larger conspiracy

that possibly involved

federal law enforcement

agencies, " and added:

"Fauntroy said he kept

silent about his

suspicions because of

fear for himself and his

family."

Fauntroy told me that

when he left Congress in

1991 he had the

opportunity to read

through his files on the

King assassination,

including raw materials

that he'd never seen

before. Among them was

information from J.

Edgar Hoover's logs.

There he learned that in

the three weeks before

King's murder the FBI

chief held a series of

meetings with "persons

involved with the CIA

and military

intelligence in the

Phoenix operation in

Southeast Asia." Why?

Fauntroy also discovered

there had been Green

Berets and military

intelligence agents in

Memphis when King was

killed. "What were they

doing there?" he asked.

When Fauntroy had talked

about his decision to

write a book about what

he'd "uncovered since

the assassination

committee closed down,"

he was promptly

investigated and charged

by the Justice

Department with having

violated his financial

reports as a member of

Congress. His lawyer

told him that he could

not understand why the

Justice Department would

bring up a charge on the

technicality of one

misdated check. Fauntroy

said he interpreted the

Justice Department's

action to mean: "Look,

we'll get you on

something if you

continue this way. . . .

I just thought: I'll

tell them I won't go and

finish the book, because

it's surely not worth

it."

At the conclusion of his

trial testimony,

Fauntroy also spoke

about his fear of an FBI

attempt to kill James

Earl Ray when he escaped

from Tennessee's Brushy

Mountain State

Penitentiary in June

1977. Congressman

Fauntroy had heard

reports about an FBI

SWAT team having been

sent into the area

around the prison to

shoot Ray and prevent

his testifying at the

HSCA hearings. Fauntroy

asked HSCA chair Louis

Stokes to alert

Tennesssee Governor Ray

Blanton to the danger to

the HSCA's star witness

and Blanton's most

famous prisoner. When

Stokes did, Blanton

called off the FBI SWAT

team, Ray was caught

safely by local

authorities, and in

Fauntroy's words, "we

all breathed a sigh of

relief."

The Memphis jury also

learned how a 1993-98

Tennessee State

investigation into the

King assassination was,

if not a cover-up, then

an inquiry noteworthy

for its lack of

witnesses. Lewis

Garrison had subpoenaed

the head of the

investigation, Mark

Glankler, in an effort

to discover evidence

helpful to Jowers's

defense. William Pepper

then cross-examined

Glankler on the

witnesses he had

interviewed in his

investigation:

Q. (BY MR. PEPPER)

Mr. Glankler, did

you interview Mr.

Maynard Stiles,

whose testifying --

A. I know the name,

Counselor, but I

don't think I took a

statement from

Maynard Stiles or

interviewed him. I

don't think I did.

Q. Did you ever

interview Mr. Floyd

Newsum?

A. Can you help me

with what he does?

Q. Yes. He was a

black fireman who

was assigned to

Station Number 2.

A. I don't recall

the name, Counsel.

Q. All right. Ever

interview Mr.

Norvell Wallace?

A. I don't recall

that name offhand

either.

Q. Ever interview

Captain Jerry

Williams?

A. Fireman also?

Q. Jerry Williams

was a policeman. He

was a homicide

detective.

A. No, sir, I don't

-- I really don't

recall that name.

Q. Fair enough. Did

you ever interview

Mr. Charles Hurley,

a private citizen?

A. Does he have a

wife named Peggy?

Q. Yes.

A. I think we did

talk with a Peggy

Hurley or attempted

to.

Q. Did you interview

a Mr. Leon Cohen?

A. I just don't

recall without --

Q. Did you ever

interview Mr. James

McCraw?

A. I believe we did.

He talks with a

device?

Q. Yes, the voice

box..

A. Yes, okay. I

believe we did talk

to him, yes, sir.

Q. How about Mrs.

Olivia Catling, who

has testified --

A. I'm sorry, the

last name again.

Q. Catling, C A T L

I N G.

A. No, sir, that

name doesn't --

Q. Did you ever

interview Ambassador

Andrew Young?

A. No, sir.

Q. You didn't?

A. No, sir, not that

I recall.

Q. Did you ever

interview Judge

Arthur Hanes?

A. No, sir.

So it goes -- downhill.

The above is Glankler's

high-water mark: He got

two out of the first ten

(if one counts Charles

and Peggy Hurley as a

yes). Pepper questioned

Glankler about 25 key

witnesses. The jury was

familiar with all of

them from prior

testimony in the trial.

Glankler could recall

his office interviewing

a total of three. At the

twenty-fifth-named

witness, Earl Caldwell,

Pepper finally let

Glankler go:

Q. Did you ever

interview a former

New York Times

journalist, a New

York Daily News

correspondent named

Earl Caldwell?

A. Earl Caldwell?

Not that I recall.

Q. You never

interviewed him in

the course of your

investigation?

A. I just don't

recall that name.

MR. PEPPER: I have

no further comments

about this

investigation -- no

further questions

for this

investigator.

|

Pepper

went a step beyond

saying government

agencies were

responsible for the

assassination. To whom

in turn were those

murderous agencies

responsible? Not so much

to government officials

per se, Pepper asserted,

as to the economic

powerholders they

represented who stood in

the even deeper shadows

behind the FBI, Army

Intelligence, and their

affiliates in covert

action. By 1968, Pepper

told the jury, "And

today it is much worse

in my view" -- "the

decision-making

processes in the United

States were the

representatives, the

footsoldiers of the very

economic interests that

were going to suffer as

a result of these times

of changes [being

actived by King]."

To say that U.S.

government agencies

killed Martin Luther

King on the verge of the

Poor People's Campaign

is a way into the deeper

truth that the economic

powers that be (which

dictate the policies of

those agencies) killed

him. In the Memphis

prelude to the

Washington campaign,

King posed a threat to

those powers of a

non-violent

revolutionary force.

Just how determined they

were to stop him before

he reached Washington

was revealed in the

trial by the size and

complexity of the plot

to kill him.

|

The vision behind the

trial

In his sprawling, brilliant

work that underlies the

trial, Orders to Kill

(1995), William Pepper

introduced readers to most

of the 70 witnesses who took

the stand in Memphis or were

cited by deposition, tape,

and other witnesses. To keep

this article from reading

like either an encyclopedia

or a Dostoevsky novel, I

have highlighted only a few.

(Thanks to the

King Center, the full

trial trascript is available

online at

http://www.thekingcenter.com/tkc/trial.html.)

What Pepper's work has

accomplished in print and in

court can be measured by the

intensity of the media

attacks on him, shades of

Jim Garrison. But even

Garrison did not gain the

support of the Kennedy

family (in his case) or

achieve a guilty verdict.

The Memphis trial has opened

wide a door to our

assassination politics.

Anyone who walks through it

is faced by an either/or: to

declare naked either the

empire or oneself.

The King family has chosen

the former. The vision

behind the trial is at least

as much theirs as it is

William Pepper's, for

ultimately it is the vision

of Martin Luther King Jr.

Coretta King explained to

the jury her family's

purpose in pursuing the

lawsuit against Jowers:

"This is not about money.

We're concerned about the

truth, having the truth come

out in a court of law so

that it can be documented

for all. I've always felt

that somehow the truth would

be known, and I hoped that I

would live to see it. It is

important I think for the

sake of healing so many

people -- my family, other

people, the nation."

Dexter King, the plaintiffs'

final witness, said the

trial was about why

his father had been killed:

"From a holistic side, in

terms of the people, in

terms of the masses, yes, it

has to be dealt with because

it is not about who killed

Martin Luther King Jr., my

father. It is not

necessarily about all of

those details. It is about:

Why was he killed?

Because if you answer the

why, you will understand the

same things are still

happening. Until we address

that, we're all in trouble.

Because if it could happen

to him, if it can happen to

this family, it can happen

to anybody.

"It is so amazing for me

that as soon as this issue

of potential involvement of

the federal government came

up, all of a sudden the

media just went totally

negative against the family.

I couldn't understand that.

I kept asking my mother,

`What is going on?'

"She reminded me. She said,

`Dexter, your dad and I have

lived through this once

already. You have to

understand that when you

take a stand against the

establishment, first, you

will be attacked. There is

an attempt to discredit.

Second, [an attempt] to try

and character-assassinate.

And third, ultimately

physical termination or

assassination.'

"Now the truth of the matter

is if my father had stopped

and not spoken out, if he

had just somehow

compromised, he would

probably still be here with

us today. But the minute you

start talking about

redistribution of wealth and

stopping a major conflict,

which also has economic

ramifications . . . "

In his closing argument,

William Pepper identified

economic power as the root

reason for King's

assassination: "When Martin

King opposed the war, when

he rallied people to oppose

the war, he was threatening

the bottom lines of some of

the largest defense

contractors in this country.

This was about money. He was

threatening the weapons

industry, the hardware, the

armaments industries, that

would all lose as a result

of the end of the war.

"The second aspect of his

work that also dealt with

money that caused a great

deal of consternation in the

circles of power in this

land had to do with his

commitment to take a massive

group of people to

Washington. . . . Now he

began to talk about a

redistribution of wealth, in

this the wealthiest country

in the world."

Pepper went a step beyond

saying government agencies

were responsible for the

assassination. To whom in

turn were those murderous

agencies responsible? Not so

much to government officials

per se, Pepper asserted, as

to the economic powerholders

they represented who stood

in the even deeper shadows

behind the FBI, Army

Intelligence, and their

affiliates in covert action.

By 1968, Pepper told the

jury, "And today it is much

worse in my view" -- "the

decision-making processes in

the United States were the

representatives, the

footsoldiers of the very

economic interests that were

going to suffer as a result

of these times of changes

[being actived by King]."

To say that U.S. government

agencies killed Martin

Luther King on the verge of

the Poor People's Campaign

is a way into the deeper

truth that the economic

powers that be (which

dictate the policies of

those agencies) killed him.

In the Memphis prelude to

the Washington campaign,

King posed a threat to those

powers of a non-violent

revolutionary force. Just

how determined they were to

stop him before he reached

Washington was revealed in

the trial by the size and

complexity of the plot to

kill him.

Dexter King testified to the

truth of his father's death

with transforming clarity:

"If what you are saying goes

against what certain people

believe you should be

saying, you will be dealt

with -- maybe not the way

you are dealt with in China,

which is overtly. But you

will be dealt with covertly.

The result is the same.

"We are talking about a

political assassination in

modern-day times, a domestic

political assassination. Of

course, it is ironic, but I

was watching a special on

the CIA. They say, `Yes,

we've participated in

assassinations abroad but,

no, we could never do

anything like that

domestically.' Well, I don't

know. . . . Whether you call

it CIA or some other

innocuous acronym or agency,

killing is killing.

"The issue becomes: What do

we do about this? Do we

endorse a policy in this

country, in this life, that

says if we don't agree with

someone, the only means to

deal with it is through

elimination and termination?

I think my father taught us

the opposite, that you can

overcome without violence.

"We're not in this to make

heads roll. We're in this to

use the teachings that my

father taught us in terms of

nonviolent reconciliation.

It works. We know that it

works. So we're not looking

to put people in prison.

What we're looking to do is

get the truth out so that

this nation can learn and

know officially. If the

family of the victim, if

we're saying we're willing

to forgive and embark upon a

process that allows for

reconciliation, why can't

others?"

When pressed by Pepper to

name a specific amount of

damages for the death of his

father, Dexter King said,

"One hundred dollars."

The Verdict

The jury returned with a

verdict after two and

one-half hours. Judge James

E. Swearengen of Shelby

County Circuit Court, a

gentle African-American man

in his last few days before

retirement, read the verdict

aloud. The courtroom was now

crowded with spectators,

almost all black.

"In answer to the question,

`Did Loyd Jowers participate

in a conspiracy to do harm

to Dr. Martin Luther King?'

your answer is `Yes.'" The

man on my left leaned

forward and whispered

softly, "Thank you, Jesus."

The judge continued: "Do you

also find that others,

including governmental

agencies, were parties to

this conspiracy as alleged

by the defendant?' Your

answer to that one is also

`Yes.'" An even more

heartfelt whisper: "Thank

you, Jesus!"

|

Perhaps

the lesson of the King

assassination is that

our government

understands the power of

nonviolence better than

we do, or better than we

want to. In the spring

of 1968, when Martin

King was marching (and

Robert Kennedy was

campaigning), King was

determined that massive,

nonviolent civil

disobedience would end

the domination of

democracy by corporate

and military power. The

powers that be took

Martin Luther King

seriously. They dealt

with him in Memphis.

Thirty-two years

after Memphis, we know

that the government that

now honors Dr. King with

a national holiday also

killed him. As will once

again become evident

when the Justice

Department releases the

findings of its "limited

re-investigation" into

King's death, the

government (as a

footsoldier of corporate

power) is continuing its

cover-up -- just as it

continues to do in the

closely related murders

of John and Robert

Kennedy and Malcolm X.

|

David Morphy, the only juror to grant an

interview, said later: "We

can look back on it and say

that we did change history.

But that's not why we did

it. It was because there was

an overwhelming amount of

evidence and just too many

odd coincidences.

"Everything from the police

department being pulled

back, to the death threat on

Redditt, to the two black

firefighters being pulled

off, to the military people

going up on top of the fire

station, even to them going

back to that point and

cutting down the trees. Who

in their right mind would go

and destroy a crime scene

like that the morning after?

It was just very, very odd."

I drove the few blocks to

the house on Mulberry

Street, one block north of

the Lorraine Motel (now the

National Civil Rights

Museum). When I rapped

loudly on Olivia Catling's

security door, she was

several minutes in coming.

She said she'd had the flu.

I told her the jury's

verdict, and she smiled. "So

I can sleep now. For years I

could still hear that shot.

After 31 years, my mind is

at ease. So I can sleep now,

knowing that some kind of

peace has been brought to

the King family. And that's

the best part about it."

Perhaps the lesson of the

King assassination is that

our government understands

the power of nonviolence

better than we do, or better

than we want to. In the

spring of 1968, when Martin

King was marching (and

Robert Kennedy was

campaigning), King was

determined that massive,

nonviolent civil

disobedience would end the

domination of democracy by

corporate and military

power. The powers that be

took Martin Luther King

seriously. They dealt with

him in Memphis.

Thirty-two years after

Memphis, we know that the

government that now honors

Dr. King with a national

holiday also killed him. As

will once again become

evident when the Justice

Department releases the

findings of its "limited

re-investigation" into

King's death, the government

(as a footsoldier of

corporate power) is

continuing its cover-up --

just as it continues to do

in the closely related

murders of John and Robert

Kennedy and Malcolm X.

The faithful in a nonviolent

movement that hopes to

change the distribution of

wealth and power in the

U.S.A. -- as Dr. King's

vision, if made real, would

have done in 1968 -- should

be willing to receive the

same kind of reward that

King did in Memphis. As each

of our religious traditions

has affirmed from the

beginning, that recurring

story of martyrdom

("witness") is one of

ultimate transformation and

cosmic good news.

The above

story was found freely

published at

http://www.ratical.org/ratville/JFK/MLKconExp.htm

on the Internet on

1/15/2011l and this single

copy is archived solely

in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

All copyrighted work in the American USSR Library is archived under fair use without profit or payment to those

who have expressed a prior interest in reviewing the included information for

personal use, non-profit research and educational purposes only.

Ref.

http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

Current Rotating

Archive of Arrests and Harrassment

of Martin Luther King Jr. at Google.com

How to Donate to

American USSR

Archived for Educational

Purposes only Under U.S.C. Title 17 Section 107

by American USSR Library at

http://www.americanussr.com

*COPYRIGHT NOTICE**

In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, any copyrighted work in the American USSR Library is archived here under fair use without profit or payment to those

who have expressed a prior interest in reviewing the included information for

personal use, non-profit research and educational purposes only.

Ref.

http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

If you have additions

or suggestions

Email American USSR Library

|