Aaron Burr, Jr. (February 6, 1756 � September 14,

1836) was an important political figure in the early history

of the

United States of America. After serving as a

Continental Army officer in the

Revolutionary War, Burr became a successful lawyer and

politician. He was elected twice to the

New York State Assembly (1784�1785, 1798�1799),[1]

was appointed

New York State Attorney General (1789�1791), won

election again as a

United States Senator (1791�1797) from New York, and

reached the high point of his career as the

third

Vice President of the United States (1801�1805), under

President

Thomas Jefferson. Despite these accomplishments and

others, including his progressive views against slavery[2]

and in favor of equal rights for women,[3]

Burr is mainly remembered as the man who killed

Alexander Hamilton in the famous

1804 duel.BiographyEarly life

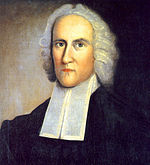

Burr's grandfather,

Jonathan Edwards

Burr was born in Newark, New Jersey, to the Reverend Aaron Burr, Sr., a Presbyterian minister and second president of the College of New Jersey in Newark (which moved in 1756 to Princeton and later became Princeton University). His mother, Esther Edwards, was the daughter of Jonathan Edwards, the famous Calvinist theologian. The Burrs also had a daughter, Sarah, who married Tapping Reeve, founder of the Litchfield Law School in Litchfield, Connecticut. Aaron Burr's father died in 1757 and his mother the following year, leaving him an orphan at age two. Grandfather Edwards and his wife Sarah also died that year; young Aaron and his sister Sally went to live with the William Shippen family in Philadelphia. In 1759, the children's guardianship was assumed by twenty-one-year-old uncle Timothy Edwards. The next year, Edwards married Rhoda Ogden and moved to Elizabeth, New Jersey. Rhoda's younger brothers Aaron and Matthias became the boy's playmates and lifelong friends. At age thirteen, Aaron Burr was admitted to the College of New Jersey in Princeton. He received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1772, but changed his career path two years later and began the study of law with his brother-in-law Reeve. When, in 1775, news reached Litchfield of the clashes with British troops at Lexington and Concord, Burr's studies were put on hold while he went to join the Continental Army. Military serviceDuring the Revolutionary War, Burr took part in Colonel Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec, an arduous trek of over 300 miles (480 km) through the wilderness of what is now Maine. Upon arriving before the city of Quebec, Burr was sent up the Saint Lawrence River to reach General Richard Montgomery, who had taken Montreal, and escorted him to Quebec. Montgomery promoted Burr to captain and made him an aide-de-camp. Although Montgomery was killed while attempting to capture the city of Quebec during a fierce snow storm on December 31, 1775, Burr distinguished himself with brave actions against the British. Burr's courage made him a national hero and earned him a place on Washington's staff in Manhattan, but he quit after two weeks because he wanted to return to the battlefield. Never hesitant to voice his opinions, Burr may have set Washington against him; however, rumors that Washington then distrusted Burr have never been documented. General Israel Putnam took Burr under his wing; by his vigilance in the retreat from lower Manhattan to Harlem, Burr saved an entire brigade (including Alexander Hamilton, who was one of its officers) from capture after the British landing on Manhattan. In a stark departure from common practice, Washington failed to commend Burr's actions in the next day's General Orders (the fastest way to obtain a promotion in rank). Although Burr was already a nationally known hero, he never received a commendation. According to Burr's stepbrother Mathias Ogden, Burr was infuriated by the incident, which may have led to the eventual estrangement between him and Washington.[4][5] On becoming a lieutenant colonel in July 1777, Burr assumed virtual leadership of Malcolm's Additional Continental Regiment. There were approximately 300 men under Colonel William Malcolm's nominal command. The regiment successfully fought off many nighttime raids into central New Jersey by British troops sailing over from Manhattan. Later that year, during the harsh winter encampment at Valley Forge, Burr was put in charge of a small contingent guarding "the Gulf", an isolated pass commanding one approach to the camp. Burr imposed discipline there, defeating an attempted mutiny by some of the troops.[6] On June 28, 1778, at the Battle of Monmouth, Burr's regiment was devastated by British artillery, and in the day's terrible heat, Burr suffered heat stroke from which he would never quite recover. In January 1779 Burr, in command of Malcolm's Regiment, was assigned to Westchester County, a region between the British post at Kingsbridge and that of the rebels about 15 miles (24 km) to the north. In this district, part of the larger command of General Alexander McDougall, there was much turbulence and plundering by lawless bands of both rebel and Loyalist sympathizers, and by raiding parties of ill-disciplined soldiers from both armies. Colonel Burr established a thorough patrol system, rigorously enforced martial law, and quickly restored order. He resigned from the Continental Army in March 1779 due to his continuing bad health and renewed his study of law. Though technically no longer in the service, he remained active in the war: he was assigned by General Washington to perform occasional intelligence missions for Continental generals such as Arthur St. Clair, and on July 5, 1779, he rallied a group of Yale students at New Haven along with Capt. James Hillhouse and the Second Connecticut Governors Foot Guard, in a skirmish with the British at the West River. The British advance was repulsed, forcing them to enter New Haven from Hamden. Despite these activities, Burr was able to finish his studies and was admitted to the bar at Albany in 1782. He began to practice in New York City after the British evacuated the city the following year. The Burrs lived, for the next several years, in a house on Wall Street.[7] Marriage and familyIn 1782, Aaron Burr married Theodosia Bartow Prevost, the widow of Jacques Marcus Prevost (see The Hermitage), a British army officer who had died in the West Indies during the Revolutionary War. They moved to New York City, where Burr's reputation grew as a brilliant trial lawyer. The marriage lasted until Theodosia's death from stomach cancer twelve years later. They had one child who survived birth, a daughter named Theodosia, after her mother. Burr believed in equality of the sexes, and prescribed education for his daughter in the classics, language, horsemanship and music. Born in 1783, his Theodosia became widely known for her education and accomplishments. She married Joseph Alston of South Carolina in 1801, and bore a son who died of fever at ten years of age. Theodosia died under mysterious and tragic circumstances; due either to piracy or in a shipwreck off the Carolinas in the winter of 1812-1813. Recently, the Aaron Burr Association has recognized two illegitimate children of Burr with Mary Emmons, his servant. Louisa Charlotte was born in 1788, and John Pierre Burr in 1792. At that time, Burr was still married to Theodosia, but most of the time was in Albany while serving in the state assembly. DNA testing, which might verify these claims, is not possible due to the lack of a male descendant in this line.[8] Legal and early political careerBurr served in the New York State Assembly from 1784 to 1785, but became seriously involved in politics in 1789, when George Clinton appointed him New York State Attorney General. He was also Commissioner of Revolutionary War Claims in 1791. In 1791, he was elected a U.S. Senator from New York, defeating the incumbent, General Philip Schuyler, and served there until 1797. While Burr and Jefferson served during the Washington administration, the Federal Government was resident in Philadelphia. They both roomed for a time at the boarding house of a Mrs. Payne. Her daughter Dolley, an attractive young widow, was introduced by Burr to James Madison, whom she subsequently married. Although Hamilton and Burr had long been on good personal terms, often dining with one another (Lomask, vol. 1), Burr's defeat of General Schuyler, Hamilton's father-in-law, probably drove the first major wedge into their friendship. Nevertheless, their relationship took a decade to reach a status of enmity. After being appointed commanding general of U.S. forces by President John Adams in 1798, Washington turned down Burr's application for a brigadier general's commission during the Quasi-War with France. Washington wrote, "By all that I have known and heard, Colonel Burr is a brave and able officer, but the question is whether he has not equal talents at intrigue." (Lomask vol.1) John Adams later put this situation in perspective by writing in 1815 that Washington's response was startling given his promotion of Hamilton, "the most restless, impatient, artful, indefatigable, and unprincipled intriguer in the United States, if not in the world, to be second in command under himself, and now [Washington] dreaded an intriguer in a poor brigadier."[9] Bored with the inactivity of the new U.S. Senate (Lomask vol. 1), Burr ran for and was elected to the New York State Assembly, serving from 1798 through 1799.[1] During John Adams' term as President, national parties became clearly defined. Burr loosely associated himself with the Democratic-Republicans, though he had moderate Federalist allies, such as Sen. Jonathan Dayton of New Jersey. Burr quickly became a key player in New York politics, more powerful in time than Hamilton, largely because of the Tammany Society, later to become the infamous Tammany Hall, which Burr converted from a social club into a political machine to help Jefferson reach the presidency. In 1799, Burr founded the Bank of the Manhattan Company, which in later years was absorbed into the Chase Manhattan Bank, which in turn became part of JPMorgan Chase. In 1800, New York presidential electors were to be chosen by the state legislature as they had been in 1796 (for John Adams). The State Assembly was controlled by the Federalists going into the April 1800 legislative elections. In the city of New York, assembly members were to be selected on an at-large basis. Burr and Hamilton were the key campaigners for their respective parties. Burr's Republican slate of assemblymen for New York City was elected, gaining control of the legislature and in due course giving New York's electoral votes to Jefferson and helping to win the 1800 presidential election for him. This drove another wedge between Hamilton and Burr. Burr became Vice President during Jefferson's first term (1801�1805). Vice PresidencyBecause of his influence in New York City and the New York legislature, Burr was asked by Jefferson and Madison to help the Jeffersonians in the election of 1800. Burr sponsored a bill through the New York Assembly that established the Manhattan Company, a water utility company whose charter also allowed creation of a bank controlled by Jeffersonians. Another crucial move was Burr's success in getting his slate of New York City and nearby Electors to win election, thus defeating the Federalist slate, which was chosen and backed by Alexander Hamilton. This event drove a further wedge between the former friends. Burr is known as the father of modern political campaigning. He enlisted the help of members of Tammany Hall, a social club, and won the election. He was then placed on the Democratic-Republican presidential ticket in the 1800 election with Jefferson. At the time, most states' legislatures chose the members of the U.S. Electoral College, and New York was crucial to Jefferson. Though Jefferson did win New York, he and Burr tied for the presidency with 73 electoral votes each. It was well understood that the party intended that Jefferson should be president and Burr vice president, but the responsibility for the final choice belonged to the House of Representatives. The attempts of a powerful faction among the Federalists to secure the election of Burr failed, partly due to opposition by Alexander Hamilton and partly due to Burr himself, who did little to obtain votes in his own favor. He wrote to Jefferson underscoring his promise to be vice president, and again during the voting stalemate in the Congress wrote again that he would give it up entirely if Jefferson so demanded. Ultimately, the election devolved to the point where it took 36 ballots before James A. Bayard, a Delaware Federalist, submitted a blank vote. Federalist abstentions in the Vermont and Maryland delegations led to Jefferson's election as President, and Burr�s moderate Federalist supporters conceded his defeat. Upon confirmation of Jefferson�s election, Burr became Vice President of the United States, but despite his letters and his shunning of any political activity during the balloting (he never left Albany) he lost Jefferson's trust after that, and was effectively shut out of party matters. Some historians conjecture that the reason for this was Burr's casual regard for politics, and that he didn't act aggressively enough during the election tie. Jefferson was tight-lipped in private about Burr, so his reasons are still not entirely clear. However, Burr's even-handed fairness and his judicial manner as President of the Senate were praised even by some of his enemies, and he fostered some time-honored traditions regarding that office. Historian Forrest MacDonald has credited Burr's judicial manner in presiding over the impeachment trial of Justice Samuel Chase with helping to preserve the principle of judicial independence that was established by Marbury v. Madison in 1803. It was written by one Senator that Burr had conducted the proceedings with the "impartiality of an angel and the rigor of a devil." Burr's farewell in March 1805 moved some of his harshest critics in the Senate to tears. However, except for short quotes and descriptions of the address, which defended America's system of government, it was never recorded in full. Duel with Alexander Hamilton

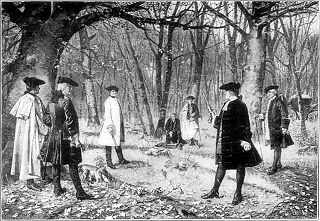

Main article:

Burr�Hamilton duel

Alexander Hamilton fights his fatal duel

with Vice President Aaron Burr.

When it became clear that Jefferson would drop Burr from his ticket in the 1804 election, the Vice President ran for the governorship of New York instead. Burr lost the election, and blamed his loss on a personal smear campaign believed to have been orchestrated by his own party rivals, including New York governor George Clinton. Hamilton also opposed Burr, due to his belief that Burr had entertained a Federalist secession movement in New York. He called Burr "a dangerous man, and one who ought not be trusted with the reins of government," and on occasion compared him to Catiline. Burr, however, felt that Hamilton went too far at one political dinner, where he said that he could express a "still more despicable opinion" of Burr. After a letter regarding the incident written by Dr. Charles D. Cooper was published in the Albany Register, Burr sought an explanation from Hamilton. Instead Hamilton responded casually by educating Burr on the many possible meanings of despicable, enraging and embarrassing Burr. Burr then demanded that Hamilton recant or deny anything he might have said regarding Burr�s character over the past 15 years, but Hamilton, having already been disgraced by the Maria Reynolds scandal and ever mindful of his own reputation and honor, did not. Burr responded by challenging Hamilton to personal combat under the code duello, the formalized rules of dueling. Hamilton's eldest son, Philip, had died in a duel in 1801. Although still quite common, dueling had been outlawed in New York, and the punishment for conviction of dueling was death. It was illegal in New Jersey as well, but the consequences were less severe. On July 11, 1804, the enemies met outside of Weehawken, New Jersey, and following the duel Hamilton was mortally wounded. There has been some controversy as to the claims of Burr and Hamilton's seconds. While one party indicates Hamilton fired only because of the shock of being struck by Burr's shot�the implication being that Hamilton's shot was unintentional�the other claims that Hamilton fired first. The two sides do, however, agree that there was a 3 to 4 second interval between the first and the second shot, raising difficult questions in evaluating the two camps' versions.[10] Historian William Weir contends that Hamilton might have been undone by his own machinations: secretly setting his pistol's trigger to require only a half pound of pressure as opposed to the usual 10 pounds. Burr, Weir contends, most likely had no idea that the gun's trigger pressure could be reset.[11] Louisiana State University history professors Andrew Burstein and Nancy Isenberg concur in this view. They note that "Hamilton brought the pistols, which had a larger barrel than regular dueling pistols, and a secret hair-trigger, and were therefore much more deadly,"[12] and conclude that "Hamilton gave himself an unfair advantage in their duel, and got the worst of it anyway."[12] In any event, Hamilton's shot missed Burr, but Burr's shot was fatal. The bullet entered Hamilton's abdomen above his right hip, piercing Hamilton's liver and spine. Hamilton was evacuated to Manhattan where he lay in the house of a friend, receiving visitors until he died the following day. Burr was charged with multiple crimes, including murder, in New York and New Jersey, but was never tried in either jurisdiction. He fled to South Carolina, where his daughter lived with her family, but soon returned to Philadelphia and then on to Washington to complete his term as Vice President. He avoided New York and New Jersey for a time, but all the charges against him were eventually dropped. Conspiracy and trial

Main article:

Burr conspiracy

After Burr left the Vice-Presidency at the end of his term in 1805, he journeyed into what was then the West, areas west of the Allegheny Mountains, particularly the Ohio River Valley and the lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase drumming up support for his plans. Burr had leased 40,000 acres (160 km�) of land (the "Bastrop" lands) along the Ouachita River, in what is now Louisiana, from the Spanish government. His most important contact was General James Wilkinson, Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Army at New Orleans and Governor of the Louisiana Territory. Others included Harman Blennerhassett, who offered the use of his private island for training and outfitting Burr's expedition. Wilkinson was later proven to be a bad choice.[13] Burr saw war with Spain as a distinct possibility. In case of a war declaration, Andrew Jackson stood ready to help Burr, who would be in position to immediately join in. Burr's expedition of perhaps eighty men carried modest arms for hunting, and no materiel was ever revealed, even when Blennerhassett Island was seized by Ohio militia[14] His "conspiracy", he always avowed, was that if he settled there with a large group of (armed) "farmers" and war broke out, he would have an army with which to fight and claim land for himself, thus recouping his fortunes. However, the 1819 Adams-On�s Treaty secured Florida for the United States without a fight, and war in Texas didn't occur until 1836, the year of Burr's death. After a near-incident with Spanish forces at Natchitoches, Wilkinson decided he could best serve his conflicting interests by betraying Burr's plans to President Jefferson and to his Spanish paymasters. Jefferson issued an order for Burr's arrest, declaring him a traitor even before an indictment. Burr read this in a newspaper in the Territory of Orleans on January 10, 1807. Jefferson's warrant put Federal agents on his trail. He turned himself in to the Federal authorities twice. Two judges found his actions legal and released him. Jefferson's warrant, however, followed Burr, who then fled toward Spanish Florida; he was intercepted at Wakefield, in Mississippi Territory (now in the state of Alabama) on February 19, 1807, and confined to Fort Stoddert after being arrested on charges of treason.[15] Burr was treated well at Fort Stoddert. For example, in the evening of February 20, 1807, Burr appeared at the dinner table, and was introduced to Frances Gaines, the wife of the commandant Edmund P. Gaines and the daughter of Judge Harry Toulmin, the man responsible for the legal arrest of Burr. Mrs. Gaines and Burr played chess that evening and continued this entertainment during his confinement at the fort. Burr's secret correspondence with Anthony Merry and the Marquis of Casa Yrujo, the British and Spanish ministers at Washington, was eventually revealed. It had been to secure money and to conceal his real designs, which were to help Mexico to overthrow Spanish power in the Southwest, and to found a dynasty in what would have become former Mexican territory. This was a misdemeanor, based on the Neutrality Act of 1794 passed to block filibuster expeditions like those questionable enterprises of George Rogers Clark and William Blount. Jefferson, however, sought the highest charges against Burr. In 1807, on a charge of treason, Burr was brought to trial before the United States Circuit Court at Richmond, Virginia. His defense lawyers included Edmund Randolph, John Wickham and Luther Martin. Burr was arraigned four times for treason before a grand jury indicted him. This is surprising, because the only physical evidence presented to the Grand Jury was Wilkinson's so-called letter from Burr, proposing stealing land in the Louisiana Purchase. During the Jury's examination it was discovered that the letter was in Wilkinson's own handwriting � a "copy," he said, because he had "lost" the original. The Grand Jury threw the letter out, and the news made a laughingstock of the General for the rest of the proceedings. The trial, presided over by Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall, began on August 3. Article 3, Section 3 of the United States Constitution requires that treason either be admitted in open court, or proved by an overt act witnessed by two people. Since no two witnesses came forward, Burr was acquitted on September 1, in spite of the full force of the Jefferson administration's political influence thrown against him. Immediately afterward, he was tried on a more appropriate misdemeanor charge, but was again acquitted. The trial was a major test of the Constitution. It was a carefully watched drama (Henry Adams gives a full account in The History of the United States of America (1801-1817)) as Thomas Jefferson wanted a conviction. He challenged the authority of the Supreme Court and its Chief Justice John Marshall � an Adams appointee who clashed with Jefferson over Adams' last-minute judicial appointments. Thomas Jefferson believed that Aaron Burr's treason was obvious, and warranted a conviction. The actual case hinged on whether Aaron Burr was present at certain events at certain times and in certain capacities. Thomas Jefferson used all of his influence to get Marshall to move to conviction, but Marshall was not swayed. Historians Andrew Burstein and Nancy Isenberg write that Burr "was not guilty of treason, nor was he ever convicted, because there was no evidence, not one credible piece of testimony, and the star witness for the prosecution had to admit that he had doctored a letter implicating Burr."[12] Later life and deathBy this point all of Burr's hopes for a political comeback had been dashed, and he fled America and his creditors for Europe, where he tried to regain his fortunes. He lived abroad from 1808 to 1812, passing most of his time in England where he occupied a house on Craven Street in London. He became a good friend, even confidant, of the English Utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, even living at Bentham's home on occasion. He also spent time in Scotland, Denmark, Sweden, Germany, and France. Ever hopeful, he solicited funding for renewing his plans for a conquest of Mexico, but was rebuffed. He was ordered out of England and Napoleon Bonaparte refused to receive him�although one of his ministers held an interview concerning Burr's aims for Spanish Florida or British possessions in the Caribbean. After returning from Europe, Burr used the surname "Edwards," his mother's maiden name, for a while to avoid creditors. With help from old friends Samuel Swartwout and Matthew L. Davis, Burr was able to return to New York and his law practice. There he lived the remainder of his life in relative peace. In 1833, at age 77, Burr married again, this time to Eliza Jumel, a wealthy widow. Soon, however, she realized her fortune was dwindling due to her husband's land speculation losses. She separated from Burr after only four months; the divorce was completed on September 14, 1836, the day of Burr's death. Burr suffered a debilitating stroke in 1834, which rendered him immobile. In 1836, Burr died on Staten Island in the village of Port Richmond. He was buried near his father in Princeton, New Jersey. CharacterAaron Burr made many friends but also some powerful enemies, and is still perhaps the most controversial of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He was indicted for murder after the death of Hamilton; arrested and prosecuted for treason by Jefferson. To his friends and family, and often to complete strangers, he was kind and generous. In her Autobiography of Jane Fairfield, the wife of the struggling poet Sumner Lincoln Fairfield, she relates how their friend Burr saved the lives of her two children, who were left with their grandmother in New York while the parents were in Boston. The grandmother was unable to provide adequate food or heat for the children and was in fear for their very lives. She sought out Burr, as the only one that might be able and willing to help her. Burr "wept and replied, 'Though I am poor and have not a dollar, the children of such a mother shall not suffer while I have a watch.' He hastened on this errand, and quickly returned, having pawned the article for twenty dollars, which he gave to make comfortable my precious babies."[16] In his later years in New York, he provided money and education for several children, earning their lifelong affection. Burr believed women to be intellectually equal to men, and hung a portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft over his mantle. The Burrs' daughter, Theodosia, was taught dance, music, several languages and learned to shoot from horseback. Until her death at sea in 1813, she remained devoted to her father. Not only did Burr advocate education for women, upon his election to the New York State Legislature, he submitted a bill to allow women to vote. Although he proved irresistible to many women, few historians doubt Burr's devotion to his first wife while she lived. He was profligate in his personal finances, and gave lip service to abolitionism even though he owned one or two slaves for a time. Burr freed one of his slaves, Seymour Burr, as a reward for his service during the American Revolution. John Quincy Adams (who was a great admirer of Jefferson) said after the former vice president's death, "Burr's life, take it all together, was such as in any country of sound morals his friends would be desirous of burying in quiet oblivion." This was his own opinion: his father, President John Adams, was an admirer and frequent defender of Burr. John Adams wrote that Burr "had served in the army, and came out of it with the character of a knight without fear and an able officer."[17] Gordon S. Wood, a leading scholar of the Revolutionary period, holds that it was Burr�s character that put him at odds with the rest of the �founding fathers,� especially Madison, Jefferson, and Hamilton, leading to his personal and political defeats and, ultimately, to his place outside the golden circle of revered revolutionary figures. Because of his habit of placing self-interest above the good of the whole, those men felt Burr represented a serious threat to the very ideals for which they had fought the Revolution. Their ideal, as particularly embodied in Washington and Jefferson, was that of �disinterested politics,� a government led by educated gentlemen who would fulfill their duties in a spirit of public virtue and without regard to personal interests or pursuits. This was the core of an Enlightenment gentleman, and Burr, his political enemies felt, lacked that essential core. Indeed, it was Hamilton�s belief that Burr�s self-serving nature made him unfit to hold office�especially the presidency. Jefferson, though one of Hamilton�s bitterest enemies, was at least a man of public virtue. This belief led Hamilton to launch his unrelenting campaign in the House of Representatives to prevent Burr�s election to the presidency, favoring his erstwhile enemy Jefferson, instead. Later in Burr�s life, Jefferson, in turn, would go so far as to push the boundaries of the Constitution in his attempt�in the charging and trying of Burr for treason�to eliminate Burr.[18] LegacyA lasting consequence of Burr's role in the election of 1800 was the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which changed the way in which vice presidents were chosen. In public and in private, Burr's behavior, even by his political foes, was labelled as considerate and gracious and he was often commended as a great listener. Although much took place in Burr's life, he is remembered by many only for the deadly duel with Hamilton. However, his establishment of guides and rules for the first Senate impeachment trial set a high moral bar for behavior and procedures in that chamber, many of which are followed today. His silence and refusal to engage in defending himself from his political critics either in legislatures or in the press, plus the fact that most of his personal papers disappeared with his daughter's death at sea and with his biographer, Matthew Davis, has left an air of mystery over his reputation. "The Aaron Burr Story", an episode in the second season of the Disney television series Daniel Boone, starred Leif Erickson as ex-Vice President Aaron Burr attempting to set up an army to take over the western states. In the show, Burr's attempt to hire one of Daniel Boone's young impressionable friends as a wilderness guide is ultimately thwarted by Daniel when a proclamation is published for Burr's arrest for treason against the United States. The historical novel Burr, written in 1973, is the first (in historic chronology) volume in Gore Vidal's Narratives of Empire series. In the comic book The Flash, a 1975 backup story featuring Green Lantern stars Burr.[19] "The Man of Destiny," written by Dennis O'Neil and drawn by Dick Dillin, reveals that Burr was recruited by aliens to act as a leader for an interplanetary society in chaos. (The alliance cloned Burr, sending the clone back to earth to duel with Hamilton and live out of the rest of "Burr"'s life on earth.) A famous "Got Milk?" commercial directed by Michael Bay features a historian obsessed with the study of Hamilton�he owns the guns and the bullet from the duel. He is called by a radio station and offered a prize if he can name the man who killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel, but he has peanut butter in his mouth and is out of milk, and cannot manage to say "Aaron Burr" clearly enough to be heard before his time runs out. In the Chris Parnell and Andy Samberg Saturday Night Live digital short "Lazy Sunday", Parnell raps "You can call us Aaron Burr from the way we're droppin' Hamiltons," referring to spending ten dollar bills (which have Hamilton's portrait on them). A boss in Super Mario Galaxy, Baron Brrr, is a reference to Aaron Burr. In Michael Kurland's "The Whenabouts of Burr" (DAW, 1975) [20] the protagonists chase across various alternate universes, trying to recover the Constitution of the United States, which has been stolen and replaced by an alternate signed by Aaron Burr instead of Alexander Hamilton. In Alexander C. Irvine's 2002 novel A Scattering of Jades, Burr takes part in a plot to bring an ancient Aztec deity into power, explaining his interest in Mexico. In M*A*S*H, there is an episode where Hawkeye Pierce and Trapper John McIntyre come off surgery, and tell Radar O'Reilly that they shouldn't be working on a holiday (Aaron Burr's birthday). Radar asks, "Who's Aaron Burr?" Hawkeye responds by stating (incorrectly), "He's the guy who shot John Wilkes Booth." Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|