Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt[1]

(May/June 1823 � July 7, 1865) was convicted of taking part

in the conspiracy to

assassinate Abraham Lincoln. Sentenced to death, she was

the first woman

executed by the

United States federal government, and was

hanged. She was the mother of

John

Surratt, who was later tried but was not convicted in

the assassination.Early lifeSurratt was born to Archibald (who died when Mary was two years old) and Elizabeth Anne Jenkins in the southern Maryland town of Waterloo. She had two brothers. As a child, Surratt was enrolled in a private Roman Catholic girl's boarding school, the Academy for Young Ladies in Alexandria, Virginia. Mary Jenkins married John Harrison Surratt, also a Roman Catholic and a farmer of French ancestry,[2] in 1839, when she was sixteen and he was twenty-seven. His family had settled in Maryland in the 18th century and the community in which they lived, Surrattsville, was named for the Surratt family. The couple had three children, Isaac (born in 1841), Elizabeth Susanna ("Anna", 1843), and John, Jr. (1844).[3] The Surratts engaged in many livelihoods over the next two decades. They farmed tobacco on a 287-acre (1.16 km2) tract purchased in 1852 and supplemented their income by operating a general store, a gristmill, a tavern, and a post office. They were nevertheless continually plagued by financial worries, problems exacerbated by John Surratt's drinking.[3][4] One biographer suggested that John Surratt was physically and emotionally abusive to his wife.[4] Following the outbreak of the American Civil War, though the border state of Maryland remained in the Union, the Surratts were Confederate sympathizers like many other Southern farmers.[citation needed] Their tavern regularly hosted fellow sympathizers, and their post office did double duty as a United States and Confederate post office.[1] The full extent of the family's involvement in clandestine Confederate activities may never be known, but it is certain (and was introduced into evidence at Mary Surratt's trial) that weapons and cash for Confederate agents were stored at the Surratt tavern, which had been leased to John Lloyd.[5] John Surratt died suddenly at the family homestead and tavern in August 1862.[3] Though the marriage had not been happy, his death left his widow far from relieved as she was in desperate circumstances financially and even in danger of eviction. The family's slaves had either run away or been repossessed (it is unknown exactly what became of them), the sale of a substantial amount of property which had given hope of resolving the financial difficulties failed because of the buyers' default, and John's many creditors still pressed to collect.[1][3] Mary leased the family farm and tavern to a former Washington, D.C., policeman named John M. Lloyd and moved with her three children to the small but well-located townhouse (at 604 H Street, NW (then 541), in the District of Columbia),[1][3][4] inherited from John Surratt's relatives and transformed its upper floor into a boardinghouse. She employed her only remaining asset in one of the few ways considered respectable for an indigent young widow; with the home's location convenient to government buildings, she was able to eke out a very modest living for herself and her family. Lincoln assassination connection

Surratt's boarding house, now housing a

restaurant in the

Chinatown neighborhood of

Washington, D.C.

Mary Surratt's older brother, Zadoc Jenkins, was arrested by Union forces for trying to prevent an occupying Federal soldier from voting in the Maryland elections that gave Lincoln a second term. Surratt's son John Surratt later admitted that he was actively involved in an earlier plot to kidnap the president, but claimed he was not involved in the assassination. After a lengthy evasion of justice and overseas capture to be returned to stand trial for the assassination of the President, John testified at his that he had been in Elmira, New York, en route to Montreal, Canada, when Lincoln was shot. He also denied that his mother had been involved in the plot in any way. On the day of the assassination, Mary rode out to her tavern with one of her boarders, Louis J. Weichmann, a young War Department clerk, who was a friend of her son, John Surratt, Jr. Although Mary Surratt claimed to have made the journey to collect back rent owed by her tenant, John Lloyd, Lloyd later testified against her, saying she gave him a package containing field glasses and told him to "make ready the shooting irons." This referred to two repeating carbines and seven revolvers that she had bought and stored for the conspirators on her property. After assassinating President Lincoln at Ford's Theatre, John Wilkes Booth did in fact first stop at the Surrattsville tavern with his accomplice David Herold. John Lloyd, the innkeeper, gave Booth and Herold whiskey, pistols, and one of two Spencer carbines as well as the field glasses. Lloyd claimed Surratt had told him to do this when she arrived earlier that day. Booth and Herold then continued traveling southward, helped by many of the same Southern sympathizers who had aided John Surratt in his activities as a courier for the Confederacy. All her accomplices were tried and either executed or jailed. Arrest and trialMary Surratt was arrested on April 17. While Surratt was being questioned by police in her boarding house, Lewis Powell, the former John Mosby's Ranger who had attempted to assassinate Secretary of State William H. Seward, appeared at her door. Although witnesses later testified Surratt had met Powell several times, thus linking her further to the conspiracy, she denied ever having seen him before. Held in military custody under sweltering conditions, Mary Surratt had her head enclosed in a padded canvas bag to prevent a suicide attempt.[citation needed] She was also kept manacled and was constantly guarded by four soldiers.[citation needed] For two weeks after her arrest and before her trial, she was held on board a warship that was being used as a prison for the conspirators.[citation needed] Her cell was sparse and equipped with only a straw pallet and a bucket. Tried by a nine-member military commission beginning on May 9, 1865, Surratt was the oldest conspirator on trial and the only woman. During the trial, a newspaper described Mary Surratt as a rather attractive, 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) buxom, 42-year-old widow. She and Lewis Powell received the most attention from the press.[6] Defended by Frederick Aiken, who worked under Reverdy Johnson, Surratt maintained her innocence throughout the trial, denying any knowledge of the assassination plot. The evidence against her presented by the prosecution included a hidden photograph of John Wilkes Booth found in her house and bullet molds on top of her dresser. Weichmann's testimony was offered by the prosecution as evidence directly implicating Surratt in Booth's plot, although authors such as Dorothy Kunhardt have written that there is evidence the latter's testimony was suborned by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.[7] The trial of the alleged conspirators continued until late June, following which the nine-member commission deliberated its verdict on June 28 and 29. On June 30, Surratt was sentenced to death by hanging for treason, conspiracy, and plotting murder, although the court attached to its finding a recommendation of commutation of her death sentence to life imprisonment, because of her sex and age.[8] Also sentenced to death were Powell (also known as Payne), Herold (who stayed with Booth until his death in a Virginia tobacco barn), and George Atzerodt, who had been assigned but failed to assassinate Vice President Johnson. Despite the desperate pleas of her daughter, her priest, and her lawyer, President Andrew Johnson signed her death warrant.[8] Johnson later denied seeing the military judges' recommendation that Surratt's sentence be commuted to life imprisonment, but presiding judge Joseph Holt said that Johnson read the recommendation and discussed it with him. Johnson, according to Holt, said in signing the death warrant that she had "kept the nest that hatched the egg".[8] ExecutionAt noon on July 6, Surratt was informed she would be hanged the next day. She wept profusely. She was joined shortly by a Roman Catholic priest, her daughter Anna, and a few friends. She was allowed to wear looser handcuffs and leg irons during this period, but was kept hooded. She spent the night praying and refused breakfast. Her friends were ordered to leave her at 10:00 on the morning of July 7, and her heavy manacles were replaced. She spent the final hours of her life with her priest. On July 7, 1865, around 1:15 P.M., a procession, headed by the nearly fainting Mary Surratt and consisting of the four condemned prisoners (their hands manacled and legs chained with heavy irons and 75-pound iron balls) and many guards, was led through the courtyard, past the condemned's newly dug graves, and up the thirteen steps to the gallows where the four were to be hanged. Surratt had to be supported by two soldiers. The actual gallows was on a ten-foot-high platform. The hangman had made Surratt's noose with five turns instead of the required seven because he had thought that the government would never hang a woman.

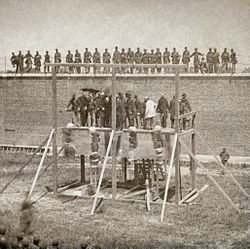

Execution of Mary Surratt,

Lewis Powell,

David Herold, and

George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865 at

Fort McNair in

Washington, D.C. Digitally restored.

The condemned were seated in chairs while their chains and shoes were removed and their wrists were tied together behind them, their arms were bound to their sides, and their ankles and thighs tied together. Instead of rope, white cloth was used. Surratt wore a long black dress and black veil. The doomed party was attended by several members of the clergy. In addition to the military personnel and various officials, one hundred civilian spectators with tickets were present to watch them die. From the scaffold, Powell said, "Mrs. Surratt is innocent. She doesn't deserve to die with the rest of us".[9] The condemned were then moved forward past the "break," (the forward part of the hinged platform of the gallows), nooses were placed around their necks, and thin white cotton "hanging-cap" hoods were placed over their heads. Mary Surratt's last words, spoken to a guard as he put the noose around her neck, were purported to be, "please don't let me fall".[9] Journalist Robert K. Elder published these as Surratt�s last words in the 2010 book Last Words of the Executed. General Winfield Scott Hancock read out the death sentences in alphabetical order. When the condemned were judged prepared, General Hancock clapped his hands twice, and by prior arrangement, two soldiers on the ground at the back of the scaffold used long poles to ram and knock out the two supporting posts, releasing the gallows platform front to fall at the hinges. The conspirators dropped about five or six feet, which apparently killed Surratt instantly, as (unlike the other condemned) after the drop, spectators saw no motion at all from Surratt's body, save natural twirling on the rope. [Atzerodt's stomach moved, but spectators judged his was the second easiest death after Surratt's. The drop clearly failed to break the necks of Powell and Herold, who from their motions both slowly strangled over the next five minutes].[10] The body of Mary Surratt and those of the other convicted conspirators were allowed to hang for about 30 minutes.[11] BurialAfter being cut down, all of the bodies were placed on the lids of their coffins (which were actually gun boxes) by the gallows, declared dead by doctors, and unceremoniously buried with the hoods still on and a glass vial containing their names to help identify the bodies. Several pieces of the rope that had ended Surratt's life and locks of her hair were sold as souvenirs. Four years later, Anna Surratt pleaded with the federal government successfully for the return of her mother's remains. Today, Mary Surratt's body is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, D.C., 1300 Bladensburg Road, NE. Her headstone reads simply, "Mrs. Surratt". The bodies of Anna Surratt and Isaac Surratt were buried on each side of their mother. John Surratt's body was buried in Baltimore. The body of John Lloyd, whose testimony may have sealed Mary's fate, is buried less than 100 yards (91 m) south of her grave, in the same cemetery (his simple tombstone is marked, "John M. Lloyd"). Surviving family and homeMary's son John was ultimately captured after a year and a half as a fugitive hiding in various Roman Catholic religious establishments as well as the Papal States.[12] In September, 1865, he traveled from St. Liboire to Montreal, to Quebec, and thence to Liverpool. He served for a brief time in the Papal Zouaves under the name John Watson. Arrested in 1866, he escaped and travelled to the Kingdom of Italy, posing as a Canadian. He booked passage to Alexandria, Egypt, and was arrested there by American officials on November 23, 1866, then extradited to the United States. He was sent home on a U.S. naval warship and put on trial. He was ultimately released after a mistrial and the statutes of limitations had run out on lesser charges. The federal government attempted to retry him but was unsuccessful. He died in 1916. Mary Surratt's boarding house still stands, in what is now the Chinatown area of Washington, D.C., housing a Chinese restaurant. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009. The Surrattsville tavern and house are historical sites run today by the Surratt Society located in Clinton, Maryland. Mary Surratt's first cousin once removed was the American novelist and short-story writer F. Scott Fitzgerald.[13] Surratt was portrayed by actress Virginia Gregg in the 1956 episode "The Mary Surratt Case", telecast as part of the NBC anthology series The Joseph Cotten Show. She is portrayed by Robin Wright in the film The Conspirator, directed by Robert Redford. It is scheduled to be released in 2011, after playing at a couple of film festivals. See also

References

Bibliography

External links

|